The story of the lean transformation of a crane manufacturer

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – In the past 15 months Terex Cranes has successfully initiated a lean transformation. Follow Catherine Chabiron on her gemba walk to see what this large company is doing to put learning at the heart of its activities.

Words: Catherine Chabiron, lean coach and member of the Institut Lean France

As I entered the General Management area of Terex Cranes – a lifting and material handling solutions company located in Zweibrücken, Germany – I saw Klaus Beulker, Senior Operations and Managing Director, and his staff doing a stand-up meeting. They stood in front of a board that carried hand-written indicators on engineering, production, quality and HR topics. "How often do you see that on the top management floor?" I wondered.

Klaus is a mechanical engineer with a long experience in industry, which started in his father's factory when he was a boy. Over the years, and prior to joining Terex, he experimented with the practical application of lean and investigated key questions on leadership and learning organization, first at Zahnradfabrik GmbH, an automotive equipment manufacturer, and later on at US-based automotive company TRW. There, he discovered a tough but impressive lean leader, Jean Luc Vidal, and learned what lean beyond the material flows is. Remember the idea of lowering the water level, so that you can see the rocks (aka the problems)? Klaus learned the hard way that when you do so you impact people directly and that you have to be around to interact with and support them by raising key questions on capabilities and behaviors.

So he regularly holds face-to-face meetings (dojos) with each of his direct reports, and tracks daily indicators in his own office. During my visit, takt time was mentioned several times: daily gemba walks for production managers, monthly hoshin workshops, staff hansei on lean efforts and results twice a year, and so on.

Refreshingly, we started our gemba walk in Engineering, where the product is designed and where customer needs or problems are discussed for each crane that is being designed. It's important to note that the takt time for cranes is not the same as takt time for cars! Larger cranes are produced at a rate of one per month, while smaller, telescopic ones (although I am not sure whether one can actually call them "small") are manufactured at a rate of one per week. This means that the learning cycles are not very short, and that the standardization process takes a bit of time. What the engineers do is list down the specifics of each order, as well as customer constraints and needs, so that the team's discussion is not so much on what features of their product or process they can change, but on how they can solve their customers' problems and meet functionality requirements.

Gradually, Terex engineers have adopted a kaizen approach, which challenges them to think and learn. Let me share a few examples :

- On a crane drawing, problems are identified on the different parts or structures of the crane, whether they are related to quality, production or other. This is a great opportunity to visually highlight areas of recurrent weaknesses.

- Problems escalated by the production floor are pulled by Engineering with a capacity limit of 10 per week (they are no longer pushed by production, which often created backlogs).

- On the recent release of a new crane model at another site at Wallerscheid, each change and their position on the crane are indicated, with illustrations (either drawing or picture) of the before and after. Changes are marked differently depending on what impact they have on the customer – positive, neutral, or negative. The next step is to release the changes using takt time, so as to reduce risk, provide benefits to the customer more quickly and, in general, increase the flexibility of the engineering team.

- I also saw some risk evaluation (FMEA) on the design changes.

Our gemba walk continued in the production area, both at Zweibrücken (where large cranes are made) and at Wallerscheid (the site producing smaller models). In the two sites, basic elements of takt, flow, quality control and kaizen are in place, even though the production areas would benefit from an improved material flow and from a train to transport components.

Here's what's Terex's manufacturing operations look like:

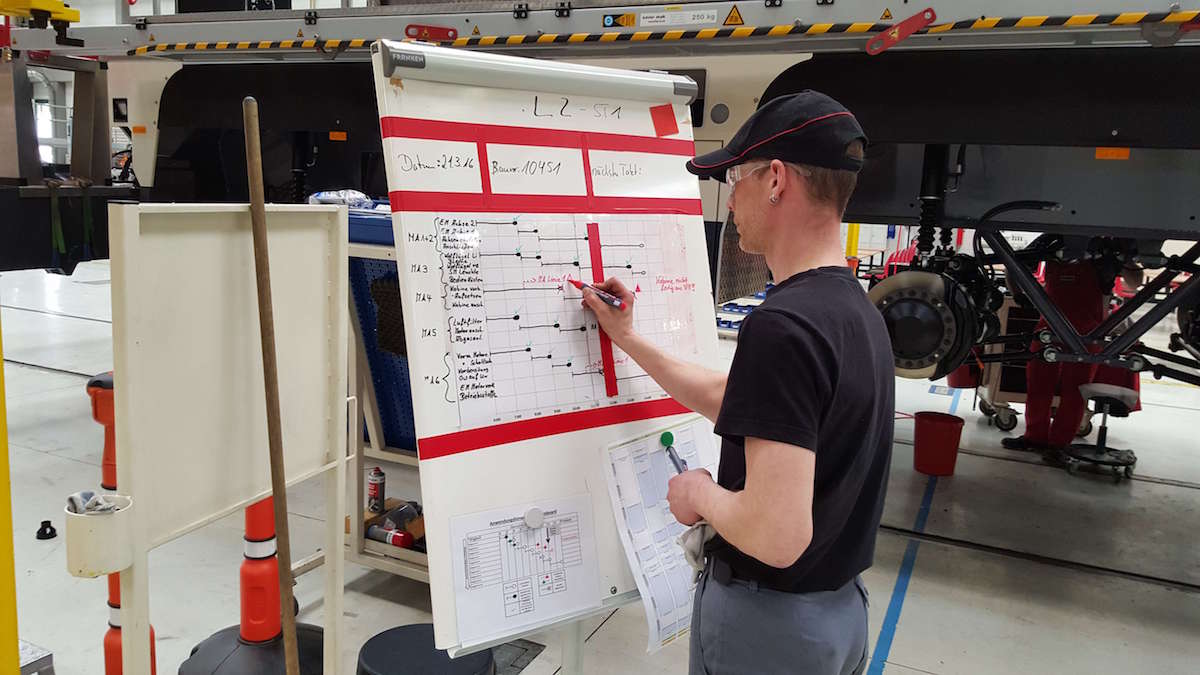

- Each assembly cell carries boards detailing the expected work for the day with hourly targets, with progress tracked by each shift.

- The assembly process, which is very complex and requires highly qualified operators who know welding, hydraulics and electronics (among other things), is still a challenge. How can you organize an andon system when no supervisor is more qualified than other operators in the cell? On the other hand, how do you convince qualified operators that they still need to learn and that help must be secured if they want to stick to takt time (on-time delivery is stable, but still far from top class)?

- While control by the operator at each step of the work is not clearly visible yet, quality gates have been positioned along the production line to prevent issues from being identified only at the final stage of inspection – the one with the customer present. The team is also focusing on problem solving and root-cause analysis.

- The whole point of the kaizen activities is to create an environment where new ideas are born, to find better ways to do things, create more efficient lines and produce higher quality products. The results are there : boom installation on the crane in Wallerscheid was re-designed based upon the suggestion of an operator to avoid complex handling, and many more suggestions are being analyzed and implemented.

- Zweibrücken also has an obeya room. It once focused solely on delivery (classic project management), while now it addresses all aspects of the process, from customer complaints to quality issues and delivery. Bringing the product into the room is undoubtedly a challenge (a crane is quite bulky), but drawings make up for it. A quick look at the boards revealed that a common bottleneck is caused by missing parts, which leads us to material planning and procurement.

Support functions are often known to observe lean efforts in production or engineering from a distance, providing support on things like milk runs or procurement when needed. Terex Cranes was the first place in which I saw a material planning office with the walls covered in boards with ongoing tasks, follow-up indicators, and even a learning corner on which a few notes on Toyota's kanban process had been jotted down. The widespread use of visual management provides a clear overview of the problems identified and the results achieved, and is testament to the company's commitment to learning.

So where is Terex Cranes at this stage? In just 15 months, the organization has witnessed a significant turnaround in operations, with inventory reduced by 27% and turns doubled. There were also slight improvements on on-time delivery. Terex has clearly initiated a lean transformation, but to me the most interesting thing about them is the extraordinary commitment to making learning continuous and lean the company's strategy – the only way to sustain a turnaround.

Once again, the role of leadership is key. If Klaus and his management team didn't arrange regular reviews, challenge their teams to achieve ambitious breakthroughs and promote collaboration between teams, there would be a risk that the key actors in the transformation, currently busy optimizing the flow of the value to the customer, revert to focusing on their own silos. Learning and leading go hand and hand in lean.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

OPINION – What happens when a senior executive jumps the fence and finds himself having to drive the very same change he was asking others to create?

VIDEO – We constantly talk about the role of leadership, but perhaps we don't realize just how intertwined leadership transformation and business transformation really are. This short video discusses why.

CASE STUDY – The author looks back at the impressive lean transformation of the Hungarian plant of Coloplast, a Danish company offering medical devices and services.

FEATURE – The future has never looked more uncertain for restaurants and cafes. The authors share a set of practical lean tips that can guide these organizations navigate the storm.