The inventory mountain

CASE STUDY — The CEO of an Italy-based hydraulic valves manufacturer recounts the company’s move from inventory-heavy uncertainty to customer-driven flow, using Kanban to collapse lead-times and eliminate warehouses.

Words: Dino Falciola

Until just a few weeks ago, if you walked through our plant in Brescia, Italy, you’d have noticed something rather strange: a “mountain” of some 170 large metal bins for milled components. These containers used to circulate endlessly around our site, until one day—thanks to our lean efforts—we stopped needing them. The pile of bins was not there because we forgot to clean up. I left it there on purpose, as a physical reminder of what we used to consider normal: huge levels of inventory, problems hidden under stock, and long lead-times that were simply considered the price of doing business.

I kept it in plain sight because the hardest thing in a lean transformation isn’t learning the tools. It’s changing the way people think. We used to think that stock would protect us from market uncertainty, bad planning, uneven demand, even our own internal uncertainty. When Lean Thinking came into the picture, however, it completely upended our beliefs system.

In this article, I’ll tell you the story of how Oleodinamica Marchesini went from a batch-and-queue, process-island factory with long lead-times to a pulled, sequenced, customer-focused assembly system where the warehouse is nothing more than a transit zone. And yes, Kanban was one of the enablers of this transformation.

UNDER PRESSURE

We have a fairly vertical structure, with upstream machining (milling and turning), a set of external processes (galvanizing, grinding, heat treatment, etc), and final assembly. We have around 750 customers and about 1,800 SKUs (we are a very clean Pareto, with 85–90 of our SKUs generating about 45% of our revenue).

Our group revenue will be around €40 million in 2026. The COVID-19 pandemic took its toll on us, and the post-COVID surge was just as challenging, with panic buying and pipelines stuffed with products. It was the time when customers doubled orders “just in case,” suppliers extended lead-times, and everyone tried to protect themselves by pushing uncertainty upstream. It was this market storm that exposed our problems.

Shortly after I joined the company at the end of 2019, things were difficult for us. We had long lead-times and frequent stock-outs, and some of our big customers were already halfway out the door. At one point, one of them handed me a report card from their supplier rating system, which quantified the money they were losing due to our stock-outs. When I saw our shortcomings translated in euros, the situation became very clear: we either improved or we’d lose our customers. That’s when we began our lean transformation.

We started with a value stream mapping exercise to identify the main bottlenecks and pain points in our process. That first mapping is etched in my memory, because the information it unearthed made my skin crawl: our average lead-time was 13 weeks. The market tolerates 4 or 5.

Our production system was classic batch-and-queue with “process islands.” There were a lot of unnecessary movement, work-in-progress, and inventory. Everything took longer than it should because there was waiting at every step in the process. At one point I asked the production director to show me the queues in front of our milling machines. One machine had 45 working days of backlog behind it. You can’t fix that with overtime. You fix that by completely changing the system.

Yet, despite these difficulties, the company was profitable. That was the trap: when you make money, there is no sense of urgency. Then private equity arrived (and I with it) and suddenly changing became existential and the cost of hiding problems in inventory unsustainable. That’s what led us to Lean Thinking: customer pressure and a healthy financial reality.

Our real constraint was capacity. We didn’t have enough of it in the right places, and we had no real-time data to even see where we were late. Coming from a small family company, we were basically a blank slate in systems and data, too. Even our ERP had gaps: missing data, poor timeliness, weak planning. We had to rebuild the backbone while we worked on operations.

We used external suppliers where needed and made internal capacity more flexible. In roughly a year we recovered enough to serve customers with shorter lead-times, as Lean helped us to drain some of the “stuffed pipelines” we were drowning in.

FROM ISLANDS TO FLOW

The biggest cultural obstacle we encountered was one-piece flow (or “one-box flow,” as we call it to make it less intimidating). When we moved toward it, some people told me I would bankrupt the company. One person even quit because they didn’t want to work that way.

Truth is, our previous way of working was no longer an option. Prior to Lean, assemblers would work in batches and it would take a long time for the first finished piece to come out of the line. We had one assembler who used to occupy about 150 square meters—three tables far apart, operations separated, material everywhere in between. After redesigning the work, that same person worked in 12 square meters and was able to build one unit from start to finish. There is more to this than a change in layout; this is a complete change in beliefs, which of course requires leadership to be present at the gemba, getting their hands dirty, and leading by example.

We also changed our approach to planning. We segmented the work and made it visible, establishing two flows: a green one for high runners and a blue one for low runners—the former needs speed and reliability, while the latter needs experience because of high product variety and infrequent demand.

As we gradually introduced flow on our lines, we started mapping our supply chain and tackling critical areas, doubling and tripling the number of internal and external suppliers to try and stabilize inbound flows.

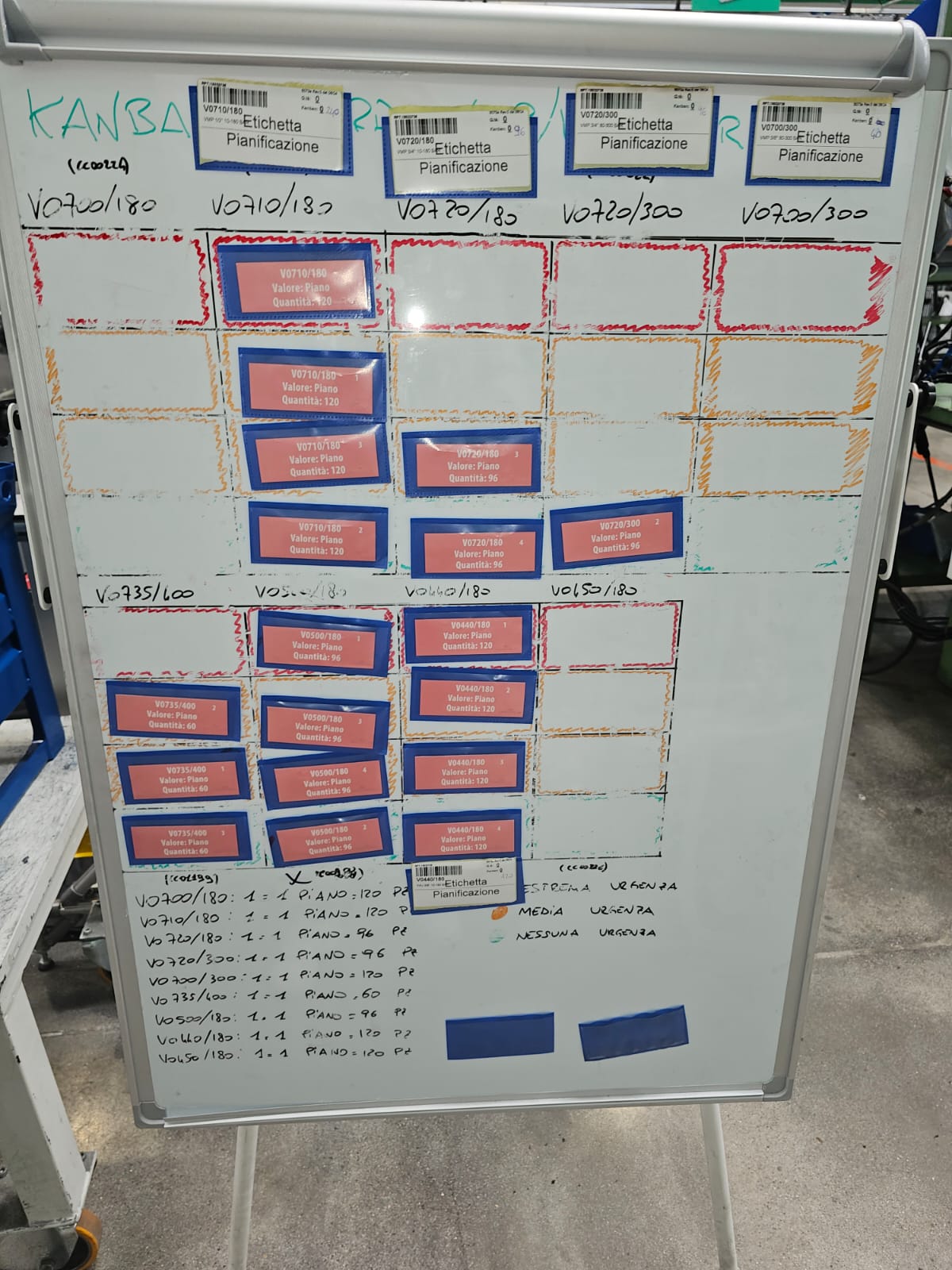

At this point, in the second half of 2023, we introduced manual Kanban. It was basically make-to-stock for high runners and make-to-order with longer waits for mid/low runners. It helped us to work through a important backlog, but it eventually hit a wall.

DIGITAL KANBAN AND AN EVAPORATING WAREHOUSE

We managed Kanban physically at the pallet-layer level because that was the only unit we could control reliably. But at a certain point, physical cards alone weren’t enough: there were too much variation, too many SKUs, and a need for synchronization across lines, components, and customer orders.

We considered developing something internally, which—looking back—would have been madness. It would have cost a fortune and delivered very little. Besides, we were coming off two ERP implementations and we didn’t need another IT project.

The breakthrough came when our IT manager watched a Caterpillar video and stumbled onto a digital Kanban solution, KanbanBOX. We started using it with a limited scope, almost as an experiment. Little did we know, that experiment would become a turning point in our lean journey.

We approached the digital Kanban rollout with a weekly cadence. We started on a line that had only two items (our highest runners). When we saw that it worked, we moved to a second line with four items. With just six items, representing about 12% of company revenue, we realized that the system was beginning to flow by itself.

We used two years’ worth of data modelled in Excel at maximum granularity to decide how many Kanbans and how many boxes made sense. Then, someone suggested that perhaps we could at some point work entirely in a make-to-order fashion. “Why do we need stock at all?” they asked. At first it sounded unrealistic. Then, week after week, it became less and less so. On our highest runner, we started at 200 boxes from the previous 600; then we reduced to 90, then 30, then 14. Astonishingly, we are now at 3. In fact, we are moving to zero, after buying different box sizes so that the system can trigger work without carrying safety stock disguised as packaging.

Another turning point came when we used KanbanBOX not just to replenish stock, but to trigger customer-specific production through a specific function called “synchro”: a one-off, non-replenishing Kanban linked to a real order. By putting the customer’s name directly on the Kanban label, production, assembly, and shipping were automatically aligned around a single destination, allowing us to assemble straight onto the customer’s shipping pallet. This meant we could eliminate picking, thus cutting about four days from our lead-time. In practice, the solution became the mechanism we use to move from “produce and store” to “produce and ship,” enabling flow in our process and putting the customer at the center of everything we do.

As flow improved, something happened that we absolutely did not predict: the warehouse stopped being a warehouse and became a transit space. We now run it with two people, two electric pallet trucks, and 500 square meters less than before. We freed up 400-500 small plastic component bins and 170 large metal bins (the ones that made up the “mountain” I mentioned at the beginning of this article). We even started cancelling forklift contracts. We’re dismantling entire sections of the warehouse, reassigning some of the racks to other factories because we don’t need it anymore. That’s why I kept that mountain of bins on the shop floor as long as I did. It’s a reminder of where we were and where we are now.

Today, after a couple of years of serious lean work, we look at our mix and realize we’ve reached what we were aiming for: about two-thirds assembly-to-order, about one-third make-to-order, almost no finished goods sitting around waiting for a customer, and shorter and shorter lead-times. We have cut inventory by over €1 million since implementing kanban, and that’s huge for us. These days, we are growing by taking market share (we have closed 2025 with a healthy +8% in revenue): when your competitors need two months to fulfil orders and you can do it in four days, the market notices sooner or later.

THE UNDERLYING CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION

When stocks collapse, results improve, but something else happens at the same time: problems come rushing to the surface. They appear everywhere, because the system no longer absorbs deviations. What used to be hidden behind inventory suddenly becomes visible. That’s what Lean Thinking is about: not expecting a world without problems, but building a system where problems cannot hide.

This shift is often the hardest part for people, and it’s where leadership really needs to step up. Making problems visible means asking people to face situations they’ve spent years learning how to avoid. I remember one of our engineers spending almost a month trying to prevent a stock problem from happening at all. Eventually, I pulled him aside and said: “If you don’t let the problem happen, I’ll make it happen. I want to see the crate blocking the shelf because it’s full. Everyone needs to see it.”

At Oleodinamica Marchesini, we no longer fear problems. We rely on them and see them as opportunities, not threats. In the end, this may be the most important outcome of our lean transformation.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – Two coaches from Italian company FPZ reflect on their role helping lean thinking spread across the company and its newly-acquired businesses.

INTERVIEW – At the recent UK Lean Summit, Ian Hurst and Keith Edwards of the Toyota Lean Management Centre ran an insightful workshop on standard work. We sat down with them to discuss standardization, respect for people and waste elimination.

CASE STUDY – An insurance company in São Paulo is experiencing a complete turnaround driven by a very capable Lean Office that understands its role is to gradually make people autonomous.

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN - If you are going to succeed at one of your resolutions for 2016, let it be that of always starting off a lean transformation with a deep analysis of the work at a single point in your organization, and then escalating your efforts to reach all the factors influencing the work.

Read more

FEATURE – Inventory reduction is critical to waste elimination. Yet, many are reluctant to do it, fearing demand variability and production instability will neutralize their efforts. Grupo Sabó's story proves otherwise.

THE LEAN BAKERY – In the second video in the series, we visit the stock-free workshop of one of 365's lean bakeries and learn about quality bread, customer focus and making lives easier for bakers.

FEATURE – This story from Cape Town car dealership Halfway Ottery shows just how much eliminating stock can contribute to turning around a business by freeing up cash.

FEATURE – In the third article in his series, Christoph Roser provides a practical guide to understand the most adequate pull system to your circumstances.