Pull flow and respect for people to drive change at Thales

ARTICLE - We always talk about going to the gemba, but we often don't understand what that entails and what changes it can bring to our companies. In this article, we hear about the experience of Thales.

Words: Cécile Roche, Lean, Agile and Industrial Performance Director, Thales Group

Thales is a global technology company operating in the Aerospace, Transportation, Defence and Security markets. It employs 65,000 people in 56 countries. In 2013, the company generated revenues of €14.2 billion. With its 25,000 engineers and researchers, Thales has a unique capability to design, develop and deploy equipment, systems and services that meet the most complex security requirements.

I first met Norbert Dubost at a meeting of Thales' industrial directors. I had just been appointed Lean Director for the Group, and I had to explain to my colleagues how I was going to help them to transform our company using lean thinking.

I had barely started to talk when Norbert interrupted me and said: "We are fed up with Corporate trying to teach us how to do our job once again! I have been doing lean for years and don't need any advice..."

At first, I felt slightly uncomfortable. On the one hand, I knew very well that trying to transform a group of 68,000 people was not going to be an easy challenge (even if we planned to initially focus on the 11,000 directly involved in manufacturing) and felt a little bit discouraged. On the other hand, I had been running a lean program for four years in one of the Group's companies and felt I almost agreed with Norbert's claim, at least in principle: indeed, during my first experience with the approach, lean had been considered a program, with a clear deployment strategy, a reporting system, various workshops, and huge potential for savings. However, despite some good financial results, no real transformation had taken place.

I, for one, was convinced that we needed something else. Norbert, instead, was convinced that he needed... well, nothing.

Firstly, how do you change the way of working to make improvement a part of the job and not just something done at certain times? How do you change the way of working to introduce continuous improvement, without having people think that improvement is not business-as-usual but a nice "plus" to work on when there is time?

Secondly, how do you focus on a few relevant actions instead of complex and big action plans that are often not brought to completion? How to link the approach to the measurement of results rather than on indicators such as the number of actions completed?

Thirdly, how do you ensure sustainable cost reduction, as opposed to short term cost cutting?

In a nutshell, how do you go from a traditional improvement program called "lean" to a true lean transformation that brings you closer to success and competitiveness?

HOW WE STARTED

We first chose to focus on visual tools, problem solving and management routines available to the teams. Why?

- Visual management is a tool for transparency, autonomy, real-time information, and problem detection;

- Problem solving is a tool for people development;

- Management routines to "takt" and the speed at which to take them.

Thanks to these tools and practices, we hoped to change the DNA of industrial managers and their teams. Visual management was almost immediately well received and spread everywhere, while for problem solving we had to work harder – we had too many problems and not enough time. For gemba management, we needed champions.

I remember the comment of one of our top managers, who was attending for the first time a five-minute update in a workshop and complained about the many problems the team faced in production. A few minutes later, he added: "Now I understand the difference between this type of visual management and our old habits with boards. This time, they are here for the teams, not for the managers!"

Even though it has happened step-by-step (it is still happening!) progress has been steady and management habits have now started to change. We have also started to see some surprising first results on the floor: motivated teams, change in management behaviors, but also lead-time reductions and an increase in capacity.

At the same time we have learnt that all these practices are nothing without just-in-time. They make the company move, yes, but move where? It is not only about improving, but about what to improve, and why. Problems appear, and managers are crushed under the weight of those problems. So, how to make sense of it all?

Pull flow gives the direction by introducing a constant tension between time and quality that prioritizes problems to solve, one by one. It gives the company pace and direction.

ALL ABOUT FLOW

Thus we started to convince and train people in pull flow and to run experiments with them. Not an easy job, trust me! "Pull flow is for the automotive industry," "We are producing very specific products," "Pull flow is not adaptable to our low number of products." We had to breakdown many preconceived ideas before we could get things to work.

Norbert helped us to convince some of the teams to give pull flow a try. And that was after he started working at a site far from his house, to which he had to commute by train twice a day every day. His schedule brought a kind of "pull flow" to his life: during his commute, Norbert responded to e-mails, organizing the day in between as problems or needs surfaced. Short meetings were arranged when necessary, and he started to leave the site every day at the same time, as nobody was scheduling late meetings anymore. His work was based around his travel plans and was much more efficient and leveled as a consequence.

The first experiments with pull flow showed amazing results - 60% reduction of work in progress and an increase in service rates from 70% to 100% in an assembly workshop. We also achieved a 50% reduction in lead-time and a 70% rework reduction in the wiring department; repairs lead-time was cut by half, with variability reduced by two thirds. However – isn't there always a "however"? - we started to face new difficulties. Just-in-time is not only a challenge for manufacturing, as support functions like purchasing or logistics are also at the heart of the process. So we started to work with them as well.

Two years after we had first met, Norbert phoned me and said: "Could you help me? I understand that I am only just discovering lean, and I need support. I thought I was doing lean but we are far from a real and deep transformation." Of course, my first reaction was a somehow mocking "Really Norbert? Are you sure you need help from corporate?" But I gladly agreed to help, knowing that Norbert's call for help represented a huge opportunity for the whole Group to learn and progress. He was head of industry for all our aeronautics activities, including six different sites, and a very well-known and respected figure at Thales. Little did I know, he would become our champion for Gemba management.

GEMBA MANAGEMENT

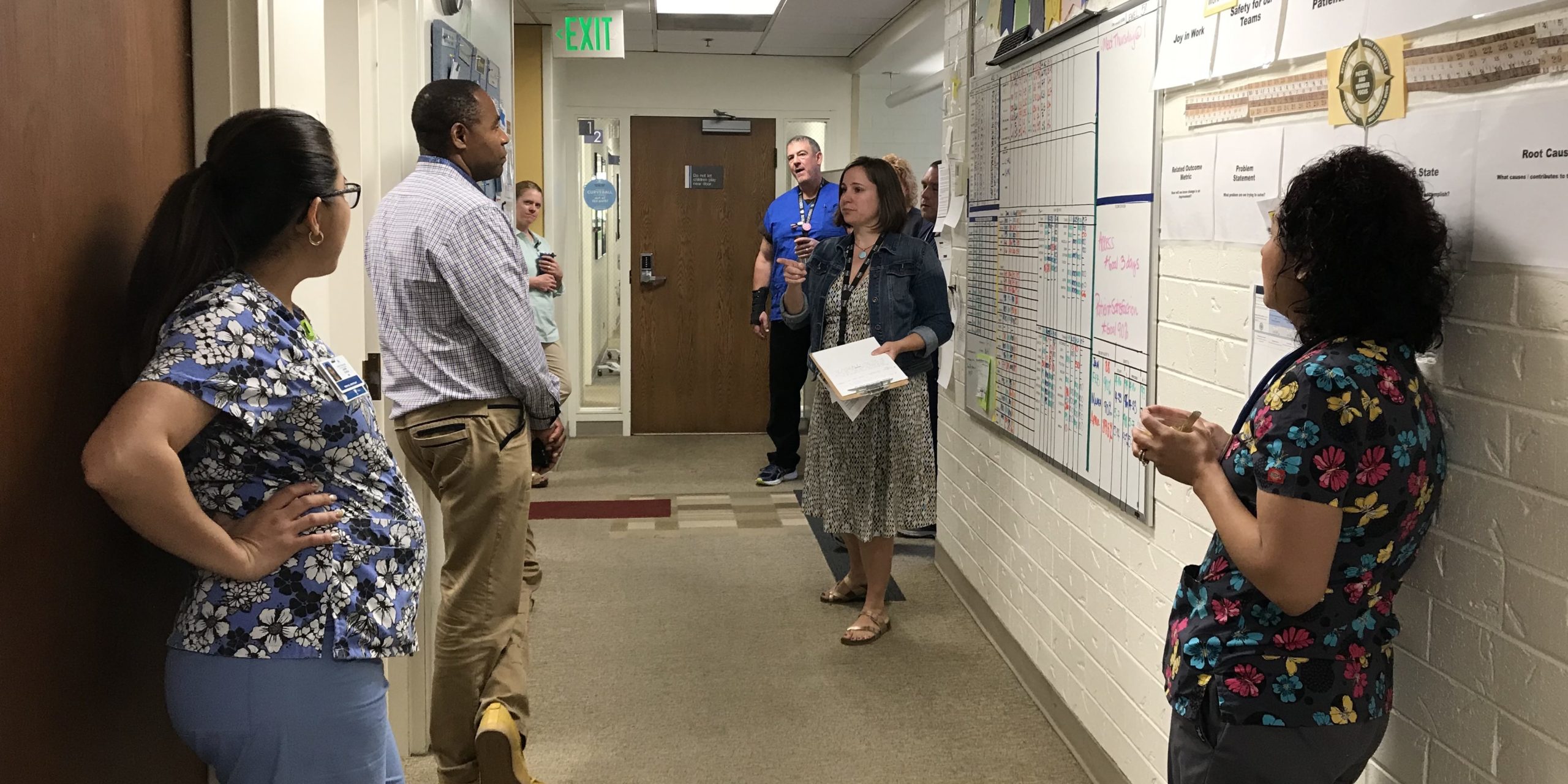

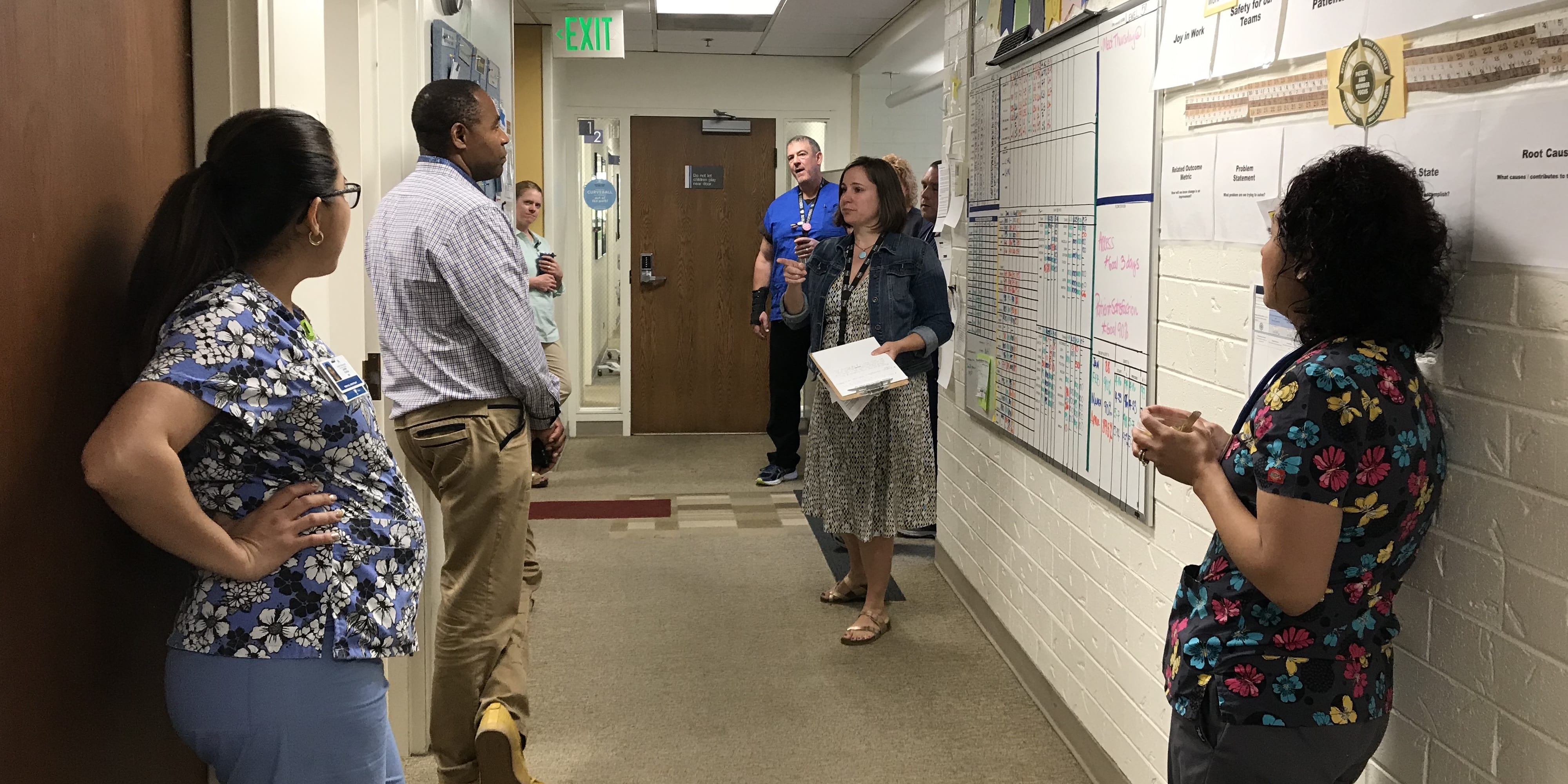

At this point, helped by a sensei, we began to discover what "going to the gemba" really means. Gemba management really is a different way of managing. The biggest change it entails is perhaps the one to your diary as a leader: going on the floor takes time, and this time must be built into your weekly schedule.

Another important lesson is that you can go on the factory floor regularly, greet people, ask them questions, and still miss what is really important. That's when learning to see gets into the picture, and that takes time.

I have found the following actions to be useful is learning to learn:

- Ask a teacher! Chose a good sensei to help you and ask you questions;

- Use pull flow as an eye opener, a way to reveal step by step the point where you are really losing money;

- Listen to people, and show respect. Think about the way you are asking questions: "What is your main problem?" is not the same as "Is everything okay?"; "Why is this equipment still there?" is not the same as "Who put this equipment there?"

- Don't try to solve everything! Deal with one problem at a time.

The main prerequisite is of course that you accept you're starting over from scratch.

Norbert's testimony is fantastic in this sense: "Going to the gemba was a huge change, first of all for me. It allows me to first see, then to understand, and to learn; finally, when you learn, you are able to influence behavioral change. Lean, and particularly going to see, was a revelation for me. It taught me the wealth that people working to produce added value for the customer represent, and made my job much more enjoyable."

Gemba walks develop everybody's leadership qualities, not only just a manager's. And a big part of leadership is developing the ability to use everybody's room for manoeuvre to the fullest. In a lean company, everyone is trained to think, not just some managers and specialists.

Of course, the lean approach is not linear. It is a chain of improvements, tests, experimentations, and learning that twists and turns, and constantly renews itself. Our experience at the gemba modifies our visual tools and practices, pull flow modifies the problems we choose to solve, and visual management takes the gemba in a different direction.

Likewise, a new leadership and management style begins with a challenge (what problem are we trying to solve?), relies on people development (how will we develop people?), increases technical skills (what is the knowledge we need our people to have in order to satisfy our customer?), focuses on the necessary improvements (how will we improve the work?), and finally establishes a new mindset.

The key here is that all of these assumptions are based on practice: putting in place different practices will change the work, and the new behaviors will in turn influence the company's strategy.

Today, Norbert is still our champion. But we need more and more Norberts, and that's what we are working towards, with some good results. At Thales, people understand that lean is a never-ending journey and that being excellent means to never be satisfied with what you have.

That is perhaps what encouraged Thales to introduce lean to engineering a year ago, but that is a different story.

For the time being, I would conclude by quoting John Shook: don't think your way into a new way of acting, but act your way into a new way of thinking!

Thanks to Norbert Dubost, VP Industrial Competence Center Thales Avionics

THE AUTHOR

Cécile Roche is Lean Director at Thales Group. An electronics engineer, over the years Cécile has led several improvement projects and managed several units in Technical Operations. Today, she shapes, deploys and supports the lean approach to production and beyond for the entire Group. She is also responsible for the development of lean facilitators.

Read more

INTERVIEW – How many times have you been asked, “What is the ROI of lean?” Jean Cunningham provides her insight to help you measure the financial impact of your lean improvements.

CASE STUDY – This hotel in Spain has been able to leverage Lean Thinking in its restaurant to successfully adapt to the new Covid-19 regulations enforced in the country, becoming more efficient along the way.

CASE STUDY – In a Brazilian insurance company, a team worked hard to streamline the revision of dental claims – a great example of Lean Thinking in an administrative process.

CASE STUDY – A physician tells PL the story of how the East Denver Medical Office became a catalyst for the lean transformation at Colorado Permanente Medical Group.