Spaghetti charts and physical distancing

FEATURE – A simple lean tool can help us create safer flows in our businesses, a critical challenge as we plan our return to work with new physical distancing measures in place.

Words and graphic: Dave Brunt, CEO, Lean Enterprise Academy - United Kingdom

“Safety first” is a well-known mantra in the business world. Protecting ourselves, our colleagues and our customers has always been paramount, but the advent of the coronavirus seems to have created a new dimension to the planning and delivery of safe processes, which will probably affect our daily lives for the foreseeable future. One of the measures our governments are trying to introduce to try and stave off the spread of Covid-19 is physical (commonly referred to as “social”) distancing. Now that in many countries the rate of infection is finally slowing down and people are turning their attention to the difficult problem of resuming their daily lives, it is clear that we are in need of creative solutions to go back to work safely. One more time, Lean Thinking comes to the rescue.

Walk into any convenience store or supermarket these days and you are likely to see visual management popping up all over the place to help ensure people maintain physical distancing while shopping. Lines on the floor two meters apart show us where we are supposed to stand – whether we are queuing to enter a store, getting our groceries or in the line waiting to pay. The impact of simple visuals is easy to see. Some places have done this better than others, of course. I am not sure why such variation exists, but here are some tips that you might find useful as you get back to work and look for ways to incorporate the new rules into your every-day activities. Whatever your organization (these suggestions apply to any workplace, not just shops), the key here is to start rethinking the work and design safe flows into our processes.

DEVELOPING SAFE FLOW

Safe flow. In the context of Covid-19, “safe” has a lot to do with distance (for which the global standard is two meters) and exposure (how long one is exposed to the virus), and we are certainly hearing a lot about this. The term “flow”, on the other hand, is not being used by the media and governments. I think it should be. For any activity, lean thinkers firstly define value through the eyes of the customer and, it goes without saying, all customers want to be safe. In the current situation, this requires time compression to ensure we are exposed to the potential risk of infection for as short a time as possible. For business owners navigating the new rules, it means enabling flow to ensure value-adding activities can be carried out one by one, without interruption – thus compressing the time it takes us customers to, for example, visit the supermarket, attend our medical appointment and subsequently receive test results back, or even have our car serviced or repaired. Not having safe flows in place risks turning activities that were once perfectly safe into dangerous opportunities for infection (not to mention, time-consuming endeavors).

To develop safe flows, here’s an easy tool that can help you to better organize your workplace and establish a check to ensure that new guidelines are followed: the spaghetti chart.

THE SPAGHETTI CHART

This is possibly the simplest and certainly one of the most visual lean techniques. It is used to make the process steps visible by following the movement of people, information or materials and drawing a line on a layout diagram to visually represent it. With the aim of understanding how to carry out the work as effectively and efficiently as we can, we usually write down the distance travelled, the number of steps and the time taken and any backflows to complete a process. We should also think about any safety issues arising from suboptimal layout or steps in our process. Spaghetti charts are a key input to the creation of standardized work charts that show worker movement and material location in relation to the physical environment.

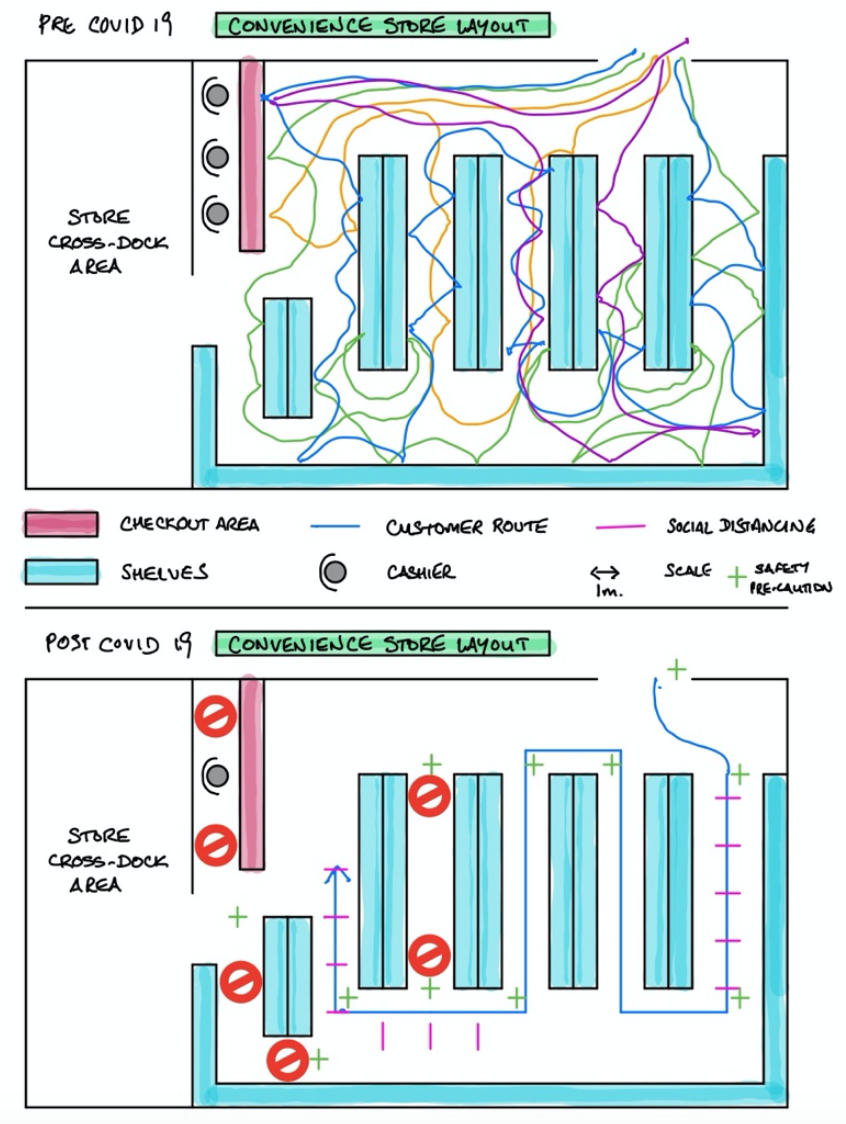

As Covid-19 spread around the world, the organizations that remained open had to respond quickly to the challenge of ensuring physical distancing between customers. The spaghetti charts in the example below show typical shopper visits to a convenience store and the flow of customers inside the store, before and after the introduction of physical distancing countermeasures. Establishing a one-way flow with physical distancing of two meters introduces the idea of standardized shopping for the first time: it no longer makes sense to place frequently bought items, such as milk and bread, at opposite corners of the store. Such layouts were never about value for the customer, only sales for the retailer. Instead, we should “level the picking” of the highest-demand items, placing them at two-meter intervals interspersed with less frequently bought products. This may smooth the flow inside the store, at a time when velocity in serving customers becomes more important than ever (less queuing means less crowds, which means less opportunities for contagion). Such flows also enable the visualization of bottlenecks – for example at the junction of particular products or at the checkout.

Designing and implementing such measures might be a headache for retailers at first, but I bet it won’t be long before they realize that strategically locating goods before products with longer picking cycle times may increase sales: while we are waiting in line, we can’t help looking around and may well decide in favor of some last-minute purchases. Imagine if a retailer changed the layout to ensure the shop was safer and quicker for you to use. Would you need to think twice before heading to that supermarket for your shopping?

But what about worker safety? There are cashiers, of course – who are increasingly seen wearing facemasks and gloves, often with Plexiglas barriers separating them from shoppers – but there are also those responsible for restocking the shelves. While replenishment is taking place, it’s very difficult to keep to the required physical distance. We are probably going to see some creative problem solving here, potentially leading to new store layouts where replenishment and customer flows are separated. Filling pick faces (the shelves) from the back, for instance, could separate shop workers from customers while enabling both to maintain physical distance. Whatever experiments are carried out, however, one-way flow will necessarily be part of the equation if we hold safety to be important to customers.

DIFFERENT ENVIRONMENT, SAME FLOW

It won’t be just supermarkets that will need to implement safe flows. Imagine attending a routine medical appointment at a GP practice, after the lockdown has been lifted. Spaghetti charting the flows could help physicians work out how to best separate patients from each other and their colleagues. Big changes have already taken place in terms of redesigning this process. Patients that contact their doctor’s practice are, first of all, given a time when a medical professional will contact them. The appointment may be by telephone or include a video consultation, its purpose being to triage the patient and determine whether or not she will need to physically see a doctor. Such a triage process dramatically reduces the number of patients who will have to physically visit the practice, which in turn reduces the risk for patients and front-line staff. For those patients who do attend an appointment in person, the safe flow starts at the door, where their temperature is checked before they are allowed in. It strikes me that Lean Thinking could help improve quality and compress time for test results, too – one by one flow always being more ideal that big centralized batch-driven approaches.

One of our car retail partners has also been working on creating a safe flow on its premises. At Meadowvale Toyota in Canada, standardized work in customer reception has been changed to enable people to follow the two-meter rule at all times. In addition, each vehicle’s controls – such as the steering wheel and gear levers – are sterilized and protected. In an attempt to apply methods that help everyone maintain a safe distance, the team at Meadowvale has established simple physical barriers, using tyres and tape, that lead customers through reception to a lounge area where they can wait for their vehicle to be repaired. From then, the designed path takes them to the payment and vehicle handover process. This is a simple but brilliant example of getting ever closer to mistake proofing (poka-yoke, we lean thinkers call it) for customers and staff.

So, Lean Thinking already has a number of tried and tested methods that support the creation of safe flows. The spaghetti chart is a key ingredient to developing standardized work and ensuring we are able to flow value to customers. With physical distancing likely to be with us for a while, it’s critical we leverage our lean knowledge to help make the work safer. After all, it’s just a new problem to solve for us.

This article is also available in Polish.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

INTERVIEW – From hospitals to start-ups, lean principles have been applied far beyond their origins at Toyota. This article discusses how lean can be applied to learning – specifically, how we can apply lean learning to learning lean.

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN - If you are going to succeed at one of your resolutions for 2016, let it be that of always starting off a lean transformation with a deep analysis of the work at a single point in your organization, and then escalating your efforts to reach all the factors influencing the work.

INTERVIEW – Toyota’s approach to developing capabilities and its focus on life-long learning are inspirational. But how do people at Toyota actually learn?

FEATURE – Construction is rife with waste, and yet lean is not widely adopted in the industry. The authors highlight how lean could benefit the sector, emphasizing the importance of developing problem-solving capabilities.