Lean crisis skills

FEATURE – In this article, Michael discusses the four levers that organizations can work on to thrive in good times… and bad times.

Words: Michael Ballé

As we enter a new period of troubled waters, it’s important to remember that crisis is both danger and opportunity (as Western legend has it, “crisis” in Chinese is written with the characters for both these words).

But how can we handle the rapids and, indeed, find the opportunity in the danger? This is a deep question leaders ask themselves when things are going awry.

The first step is, of course, to recognize – often to admit to ourselves – that we’re in a crisis. Very often we feel that if we put our heads down and keep on going, things will turn around by themselves. To be fair, sometimes they do, but in many cases the danger becomes real precisely because we’re in denial, or in sideration – not knowing what to do when the tsunami wave approaches. A back-of-the-envelope framework for this is to visualize the depth of the crisis as the time it takes to acknowledge that performance (whichever performance you look at) is going down and something will have to change to turn things around.

Moving out of this sideration requires solid problem awareness and problem-solving skills:

- What is happening?

- What usually happens in this sort of situation?

- What are the key factors to explore?

With one’s thinking hat on, it often turns out the issue is clear, but unpalatable. There is an element in the way that we’re doing business that is no longer tenable in current market conditions. For instance, if you’ve built a business riding the digitalization wave for fifteen years, developing bespoke digital systems for corporate clients, sooner or later you’ll hit a plateau where firms have digitized everything that they thought they could and at the same time interest rates rise, budgets tighten and “the rest can wait”. The market has not gone away, as people still need digital systems (actually can’t do without them by now) and these systems need both maintenance and replacement, but the urgency is gone and any project can be postponed by a year or two without the client feeling they’re losing the race. It’s pretty clear you then have to shift from selling build to selling run, as well as catch the next wave of equipment, such as Generative AI. Decisions, in fact, are less about whether to go right or left (as if you could do either freely) and more about choosing what kind of deals you can make. In changing conditions:

- What current deals are going better and which are going worse?

- How can these deals be catered to and changed if need be?

- What new partners do we need to deal with to be stronger in the new climate?

- What deals need to be stopped because they’re just holding us back?

Specific decisions (when, how) reflect deeper choices of orientation: which way are we going to be facing market conditions and with whom? And how do we make new deals stick in a way that all profit, whether new deals with customers (how we guarantee consistency of quality and price in any new offer), with our own people (how we guarantee stability of employment conditions with new market pressures), and partners (how we guarantee that they’ll make money with us in the new game). Most decisions we’ll have to make are about on-going deals: which deals are improving and need to be sustained? Which deals are worsening and what to do about that? Which deals need to be revoked and replaced with something else? A frequent mistake is to think decisions can be taken out of context and deals will adapt on their own. They rarely do. Looking at hard decisions requires also looking at whom they will impact, in terms of both the deal and the relationship.

When we have figured out what’s going on, we can then look at our processes and see how adapted they are to where the market is going. This is usually daunting, because delivery processes typically adapt to a situation and then become quite inflexible. Processes involve both systems and people and changing focus means convincing people and revamping systems, which can be intimidating. This is usually what people mean by “transformation”: change is needed and needs to be managed carefully. As we all know, not all change efforts succeed and we need to face that deep down we’re all Kodak – we know what the change should be, but the business will fight long and hard against it to maintain its status quo. At this point, the leader will have to take hard decisions and sell them to the teams.

This is where culture comes into play. Some cultures are open to change, some are not. Some are oriented toward the customer; others are obsessed with the process. Some are focused on facing problems and making staff’s work easier; others are biased to keeping bosses happy. Some are “can do” cultures; others, “no” cultures. Some are about competence; others about compliance. Whereas decisions can be expressed in rational terms, outlining goals, options and evaluating cost/benefits or benefits/risks, and processes can be mapped and designed much like engineers draw a machine, culture is a different beast. It’s far more intangible and few people are trained in handling it – so most senior executives prefer to ignore it. Culture cannot be managed but it can be shaped and steered. Culture is not about processes, systems and tools but about interpretation, transmission and a feeling of togetherness. Typically, a culture will be handled by:

- Communicating priority in goals and helping people see what is important in what they do or what they’re asked to do.

- Clarifying how each person can participate to the ultimate goal, which attitudes and behaviors help, and which hinder.

- Spelling out autonomy zones where each person can take independent decisions (and where not) and communication zones where people can share and discuss.

- Organizing the right collaborative rituals, events and work tools to support the overall effort – and the proper institutions to support these.

- Encouraging and rewarding both results towards the goal and how these results are achieved according to the culture.

- Having clear ways to deal with honest mistakes and deliberate violations.

It’s not rocket science, but it needs to be learned and practiced; and it is not so easy because the action/effect links are never particularly clear. Still, this is an essential element of how processes will be interpreted by people and applied. In lean, it’s not infrequent that tools put in place to stabilize work conditions, such as heijunka boards and kanbans, are used by some managers as pressure tool to show people they’re behind and punish them rather than help them. For instance, in the last heijunka board I saw, the new management had decided to put “real demand” cards in there to be pulled by the train from the line. Everyone knows these cards can’t be served because the components haven’t been sourced due to the usual supply chain issues, so the board will be full of red “not served” cards and people will shrug them off. This is not one red card to act as an andon (the product should have been in the shop stock but I was surprised not to find it there); this is management pressure to yell at everyone how late production is on delivery (what can I do about all these red cards, I never expected the products to be in the shop stock because I know we don’t have the components on hand). One is support – we’ve got an unexpected problem, let’s go on the line to see what is going on and how we can help – while the other is pressure – work harder or else. The tools – heijunka board, kanban cards, train, shop stock – are the same, but the intent vastly different.

The last critical element is fuzzier still. For lack of a better word, let’s call it “aura”. A culture is very largely influenced by how the leaders are perceived and this is very tricky because it works both ways: aura influences culture, but culture shapes aura as well. The halo effect is a well-known human bias by which some positive trait in a person influences how we perceive their other traits. A brilliant innovator like Steve Jobs will be forgiven for his tantrums and flaws where you and I wouldn’t be. One standout trait will influence us positively on how we judge the whole person or company. We easily reduce people to what they do best – or worse. The aura of a leader is her ability to communicate visibly her best traits and recruit people to her cause. It’s hard to describe clinically because it tends to be a blend of presence, vision, credibility, empathy, charisma and mostly visibility. Most leaders are uncomfortable with it, but it’s an essential mix of getting the ball rolling, particularly in times of crisis and change.

Facing the danger and catching the opportunity requires both luck and skill. Nothing much can be done about luck other than prayer and optimism, but the skills of leadership in a tough spot can be worked on:

Market conditions are what they are – there’s nothing much we can do to change that. The question is: how can we adapt? What are the levers we can work on to respond to the challenges markets present us? Our first step toward adaptation is to review the current deals that make our business position and figure out how theses need to change and what decisions need to be taken. This leads us to realize that our processes are set up to deliver on specific deals, are supported by ingrained systems and will need to be changed – and that change will need to be managed carefully if you want to avoid breaking the toy altogether. Which leads us into the importance of culture, and the importance of investing in a positive, growth mindset, “can do” improvement, and agile culture when things are going well – which you will really need when the tide suddenly turns, and all goes pear shaped. Finally, never underestimate the importance of leadership aura (no matter how hard to describe it might be) to succeed at turning the ship around. It is essential to draw the right people to you and influence situations you cannot control.

Decisions and deals, processes, culture, aura – these four levers can be worked on in good times and bad times, to respond to fast-moving market conditions and continue to grow sustainably and profitably in fair weather, and in foul.

THE AUTHOR

-p-500.jpeg)

Read more

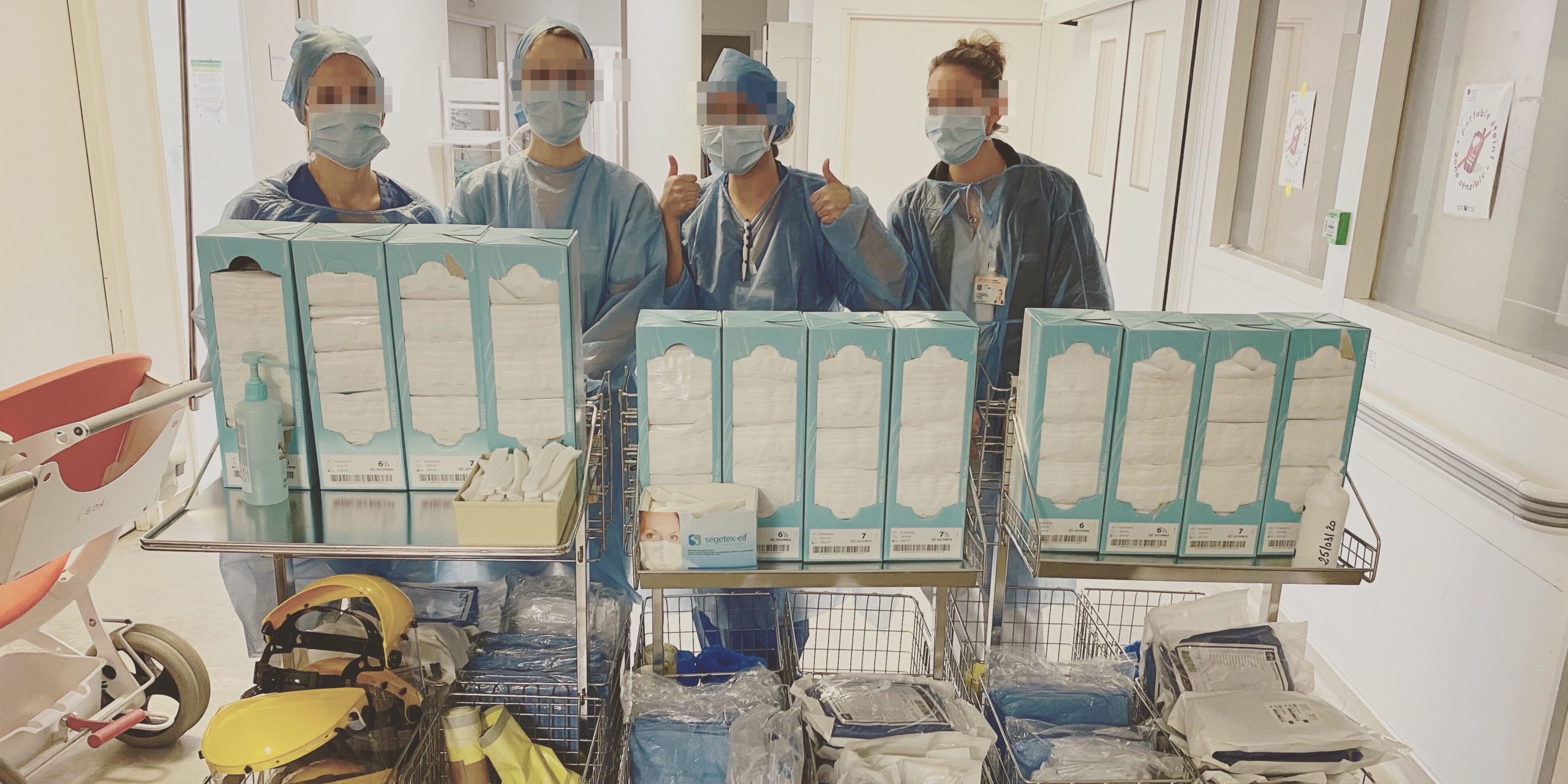

FEATURE – As Italy rolls out its vaccination campaign, the author reflects on what he recently observed at a vaccination hub in the Veneto region and discusses how the process could be made leaner.

CASE STUDY – In a Brazilian insurance company, a team worked hard to streamline the revision of dental claims – a great example of Lean Thinking in an administrative process.

PROFILE – In an industry dominated by star chefs and big egos, meeting a humble leader who has made people development his battle cry is a breath of fresh air. PL interviews Legal Sea Food’s Richard Vellante.

FEATURE – What started as the idea of two friends to meet up and discuss their lean journeys turned into a regular get-together of lean practitioners in the Cape Town area. Another example of the importance of sharing.

Read more

NOTES FROM THE (VIRTUAL) GEMBA – This small manufacturer is relying on Lean Thinking to keep the business running during the Covid-19 crisis, overcome the disruption in its supply chain, and even innovate.

NOTES FROM THE (VIRTUAL) GEMBA – This week, the author chats with an innovative insurance company as it relies on its lean learnings to ensure business continuity and switch to remote working during the Covid-19 crisis.

VIDEO INTERVIEW – We recently caught up with John Shook at the Lean Healthcare Academic Conference in Stanford and asked him to share his thought on the questions we need to ask ourselves in a lean journey and on lean in turbulent times.

CASE STUDY - In the past two years, the Consorci Sanitari del Garraf near Barcelona experienced a lean turnaround. The author gives us an overview of the key building blocks of this transformation.