Just say the word: Chorobiki

FEATURE - In this new series based on his latest book What’s Lean?, Michael Ballé explains lean terms, from the most common to the least known, to uncover the meaning and thinking behind them.

Words: Michael Ballé

Roberto Priolo: I love how some of the terms in the glossary are lesser known, almost invisible lean concepts. Let's look into chorobiki. Why is it so important and what is its relationship with kanban? I wonder... if kanban is the signal, would you say chorobiki is the habit that makes pull work day after day?

Michael Ballé: Most people intuitively understand why smaller batch sizes are a good thing. When you work in small batches, problems show up faster. If something goes wrong, you only have a small amount to fix or scrap instead of discovering the issue after producing a huge quantity. That naturally leads to better quality, because defects are caught early and corrected before they spread. Smaller batches also improve flexibility. You can adjust priorities, designs, or processes more easily because you’re not locked into finishing a large run before changing direction. This makes it easier to respond to real demand instead of forecasts, and it keeps work aligned with what customers actually need right now.

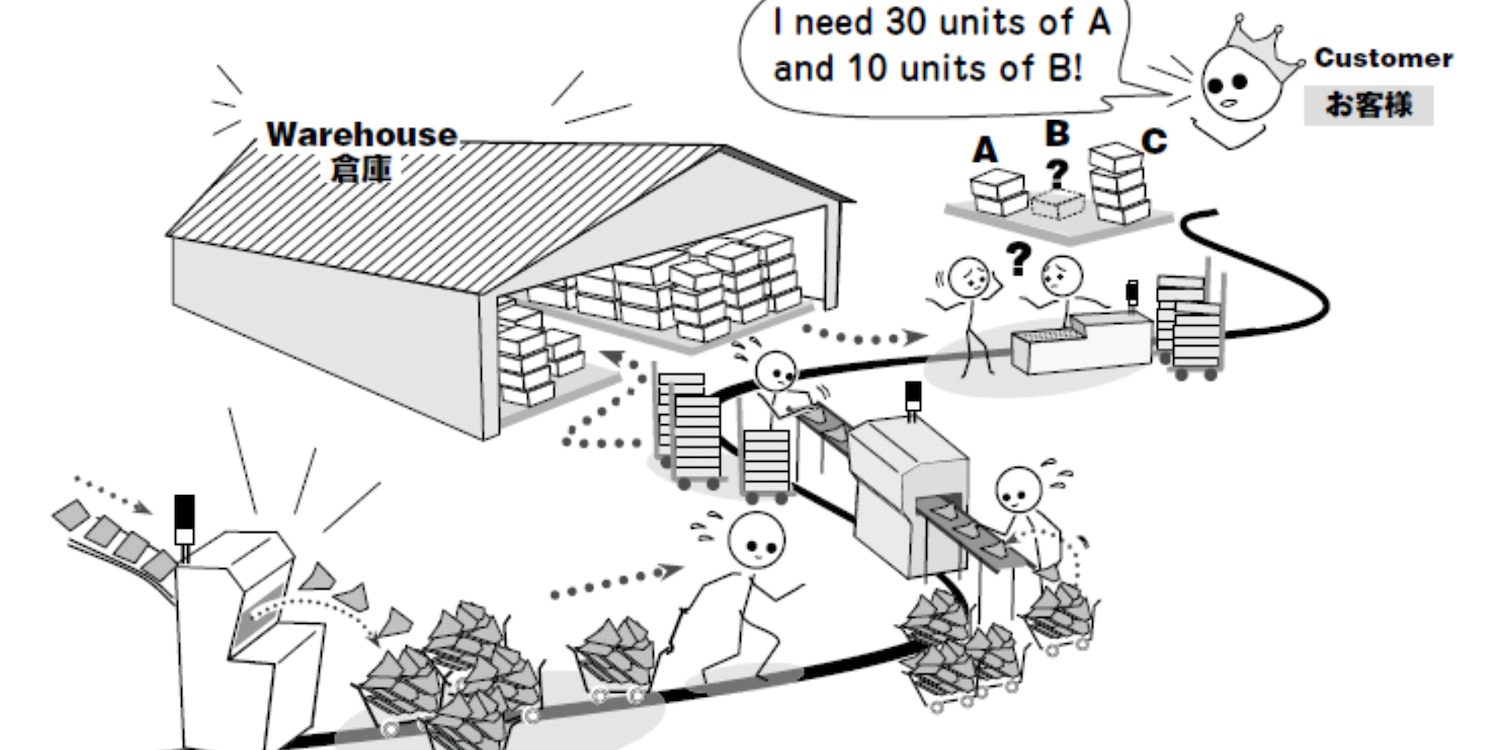

There’s also a strong delivery safety benefit. In most production environments, time spent producing item A is time not spent producing items B, C, or D. If you run long batches and something goes wrong—machine failure, quality issue, missing material—you risk running out of all the other items at the same time. Smaller batches reduce this risk by spreading production time more evenly across different references, so a single issue is less likely to disrupt everything.

What people often miss, however, is that small batches alone are not enough. There is little benefit in reducing batch sizes if you still only pull from shop stock infrequently. If replenishment is rare or irregular, you just end up with many small batches sitting idle, waiting for the next pull signal. The real benefit comes when small batch sizes are combined with frequent, regular pull from stock. Frequent pull creates fast feedback, keeps inventory moving, and ensures that the system actually reacts to consumption. Without that regular pull, smaller batches don’t improve flow—they just change the size of the piles.

In Lean, each cell owns what it produces until a customer comes and picks it up. Finishing a part does not mean the work is complete. The work is only truly finished when someone takes it and uses it. This is like a bakery, where the baker owns the croissants and pastries until a customer buys them. If a school bus full of children arrives and buys everything at once, the bakery is thrown into disarray. Shelves are suddenly empty, regular customers are disappointed, and the baker is forced into rush mode. The problem is not how the croissants are baked, but how uneven and unpredictable the purchasing is.

The same thing happens in production when parts are pulled in large, irregular batches. Even if the cell works efficiently, long gaps followed by big pulls make it hard to stay stable. Inventory piles up, then suddenly disappears, and the cell loses sight of how its work is really being consumed.

Chorobiki is the practice of purchasing parts from the cell at a regular, frequent cadence. By picking up work often and steadily, the cell can clearly see what is being used, in what order, and at what rhythm. This shows why production needs to happen in small batches that match the way parts are actually consumed. At a deeper level, chorobiki gives meaning to the work. People see that what they make is picked up regularly and used. The work moves, it matters, and it connects to someone else. It also creates a strong reason to be on time and to speak up when there is a problem, because any issue will quickly affect the next pickup.

Kanban by itself can easily turn into just another set of production instructions. Instead of a list of parts to make, the cell now has a pile of kanban cards telling it what to produce. When there is no regular pickup, these cards can accumulate into a long backlog, sometimes representing days of production. The cell simply works through the stack, disconnected from when or whether the parts are actually needed. When this happens, it sends a clear signal that no one really cares about the parts as parts. The focus shifts to completing kanban cards rather than supporting real consumption. The cell is busy, but it has no clear sense of urgency, priority, or customer impact. Kanban becomes paperwork, not pull.

Chorobiki makes kanban real. When parts are picked up at a regular, frequent rhythm, the cell sees that everything it produces is being used. Parts A, B, C, and D all move out in a visible cadence, not in big, irregular waves. Because of this rhythm, the cell can focus on a meaningful question: am I producing fast enough to keep up with consumption? Instead of worrying about clearing a backlog of cards, the cell worries about not running out of parts for delivery. Kanban stops being an abstract instruction system and becomes a living connection between production and use: sell one, make one.

Understanding chorobiki is often the watershed moment in your Lean Thinking, when people realize that the role of a cell—and even of an entire plant—is not to make parts but to deliver them. Making something that sits on a shelf is not success; delivering what is needed, at the time it is needed, is. Once this clicks, kanban is no longer about quantities or volumes. It becomes a way of managing by time. The key question shifts from “how much did we make today?” to “did we deliver what was needed at the expected time?” Time, cadence, and rhythm become more important than output totals.

This changes how production is planned. Instead of loading the system with work to keep people busy, you organize production so that it can respond reliably at each pickup. Small batches, sequencing, and quick problem-solving matter because they protect the delivery rhythm. It also changes how teams are managed. People are no longer judged mainly on how much they produce, but on how well they support on-time delivery. Problems are surfaced earlier, teamwork increases, and the purpose of the work becomes clear. The cell exists to serve its customer on time, and everyone can see when that promise is at risk.

RP: What’s the "origin story" of this cartoon?

MB: I thought of this cartoon because Santa is a perfect, and funny, example of non-chorobiki. The poor guy has to deliver presents to all the children in the world on the very same night. From a lean point of view, it is the worst possible delivery model: everything, everywhere, all at once.

This creates enormous muri and variation in the supply chain. All demand is concentrated into a single moment, so production has no choice but to work toward one massive peak. The elves may be fine working all year to build stock for one night, but the system only survives because it ignores flow and relies on a heroic effort. The waste shows up immediately after Christmas. Whatever toys were overproduced to protect against uncertainty are dumped into post-Christmas sales. Prices drop, consumption is distorted, planning gets worse the next year, and the cycle of overproduction continues. Making too much becomes the answer to not knowing exactly what will be needed.

In a chorobiki world, this would look very different. Demand would be pulled regularly, deliveries would happen at a steady rhythm, and production would mirror real consumption instead of guessing once a year. There would be far less stress, far less excess, and far more learning.

And if Santa only received the demand signal, the kanban, once he was already on the rooftop, he would truly need magic! At that point, no system can recover. Which is exactly why chorobiki matters: delivery must be organized in time, not left to last-minute miracles.

The image exaggerates, of course, but it is actually very close to how many supply chains are run. Production sites are often organized as if everything had to be delivered at once, at the last possible moment, and as if any problem had to be solved through heroics rather than design. This way of running production creates enormous waste. Huge inventories are built to protect against uncertainty, people are overburdened to hit artificial peaks, and problems are hidden until it is too late to fix them calmly. After the rush, excess stock is discounted, scrapped, or pushed onto customers who do not really need it.

What makes it worse is that most of this waste is invisible. It is treated as normal: seasonal spikes, end-of-month pushes, expediting, firefighting. Because everyone is used to it, no one really looks at how much it costs them in time, energy, money, and human effort. To me, the cartoon works because it holds up a mirror. When you laugh, you also recognize the pattern. It shows how absurd the system is, not because people are incompetent, but because delivery is not managed in time. And as long as that goes unquestioned, the waste remains gigantic and largely ignored.

There is a detailed description of chorobiki logic in The Gold Mine page 178 to 182 that shows that increasing frequency of pick-up can reduce overall inventory even before we learn to reduce batch size. This is lean magic: beat that, Santa!

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – As lean thinkers, our focus is on problem-solving. The author explains why effectively solving problems depends on our ability to make the right decisions and suggests the lean community plays closer attention to this.

CASE STUDY - HM Courts & Tribunals Service has been using lean ways of working for over six years, learning many lessons along the way and achieving some fantastic wins.

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – The author visits an SME specializing in the instalment of electrical equipment. Its CEO has learned that integrating lean in their strategy can lead to sustainable growth.

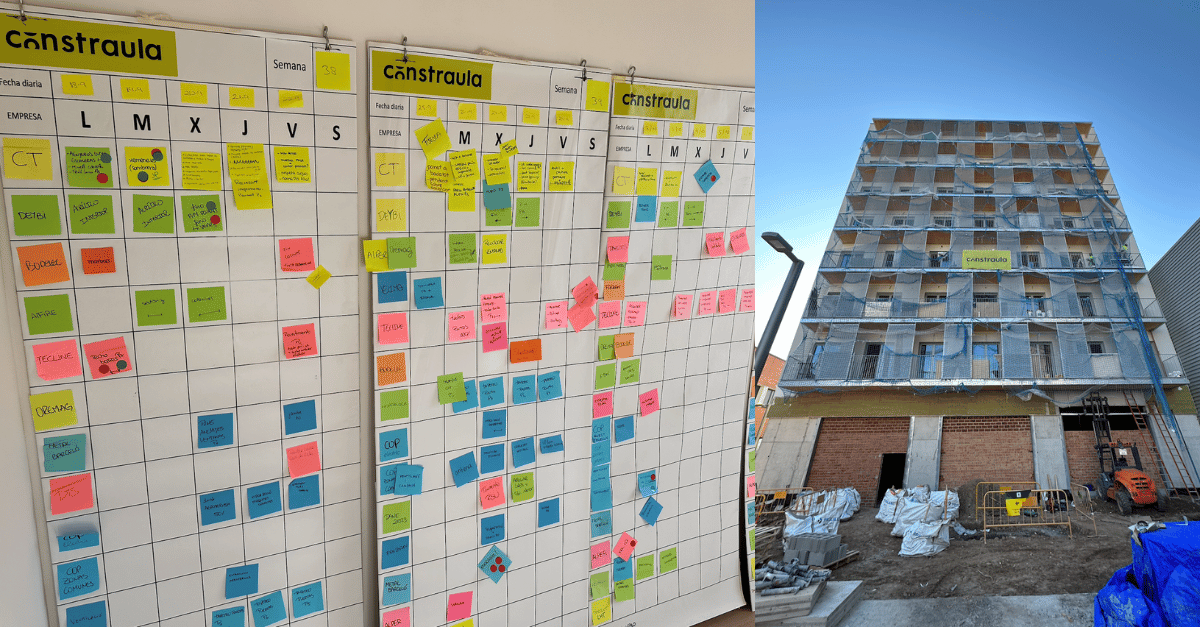

CASE STUDY – Thanks to Lean Thinking, this Spanish construction company was able to deliver a challenging project in one year, well ahead of schedule. Here’s how they did it.

Read more

FEATURE – Using an effective example from every-day life, the author discusses why Kanban is the gateway to Lean Thinking – and not just a tool.

FEATURE – The author explores the relationship between kanban and improvement and discusses how using it can impact our lean transformation.

FEATURE – The release of Christoph Roser’s new book All About Pull inspires John Shook to discuss the origins and true meaning of “pull” and why it is incorrect to blame JIT for the shortcomings of global supply chains.

FEATURE – In the last article in his series, the author discusses how you can mix and combine the different pull systems available to the lean practitioner.