How we are scaling craftsmanship

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – This article explores how Sodebo’s leaders use TPS to scale craftsmanship, improve flow, and strengthen consumer focus across operations.

Words: Catherine Chabiron

Sodebo is a food company based in Vendée, France, which currently produces 1.3 million pizzas, meal salads, pasta boxes, and fresh sandwiches every day. Having started out as a simple delicatessen and caterer’s shop in 1973, this family business is a real success story.

The company’s expansion from expert catering craftsmanship to large-scale production—now employing 3,200 people—has presented significant challenges, such as bureaucratic rigidity, a diluted consumer focus, and a greater separation between management and operations.

LEAN FOR LARGE-SCALE CRAFTSMANSHIP

Bénédicte Mercier, Marie-Laurence Gouraud, and Patricia Brochard, the founders’ three daughters who now co-manage Sodebo, have recognized this. They have been working for the past six years to rediscover the essence of craftsmanship and better satisfy their consumers (more than one in two households in France). I am returning to Sodebo today to understand how they have embarked on an exploration of the Toyota (Thinking) Production System to bring even more freshness to their products.

Bénédicte, Marie-Laurence and Patricia are quite hands-on, currently spending a third of their time, on average, dealing with the reality on the ground. As leaders, their objective is threefold: to work closely with customers, to manage flows more tightly, and to continuously improve.

They are assisted in this by Séverine Ruault, their Lean Officer, with whom I have an appointment to try to take stock, in a single day, of some of the major changes the company has undergone over the past six years.

It is impossible not to mention Just-in-Time in this company dedicated to the manufacture and delivery of fresh products, where the use-by date drives all logistical decisions.

REDUCING STAGNATION, IMPROVING COLLABORATION

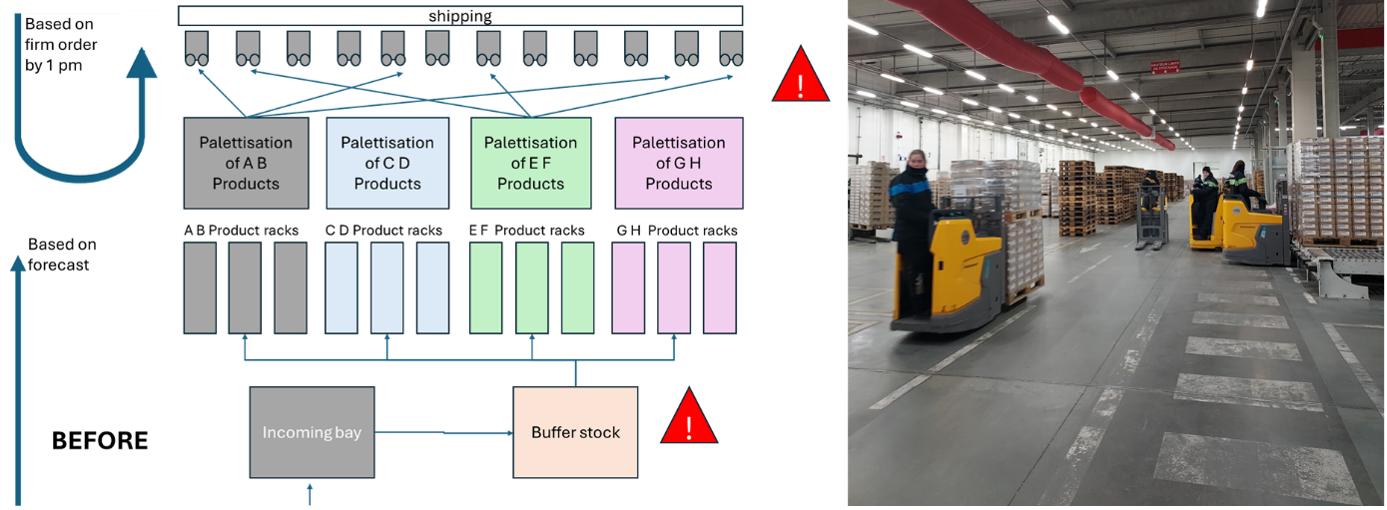

Sodebo sells its products mainly to supermarkets, which place firm orders daily by 1 PM for next-day delivery. Triggering production on demand would introduce too much variability, which would be impossible to manage on the production lines. The production flow, therefore, still relies mainly on forecasts. Only order preparation and truck loading are based on firm orders.

Séverine and I join Eric, the company’s Supply Manager, in the shipping building. He explains how his teams are helping to reduce stagnation: “We had two major problems with shipping. The first was the buffer stock near the loading bay at the entrance, where we dumped the entire production before gradually transferring it to the product storage racks. We are in the process of eliminating this buffer stock and reorganizing the unloading conveyors to go directly to the racks.”

The buffer stock area, which was full in 2018, is now empty. “If we use it,” says Séverine, “we immediately launch a root-cause analysis.”

“The other problem,” continues Eric, “was the shipping docks themselves. There are a lot of them, and our products were stored and palletized in an area nearly 150 metres wide. When we were preparing the trucks, the forklift operators kept getting in each other’s way, and we had a real safety risk.”

Instead of specializing the racks by product, Eric’s teams switched to specializing by customer. The lorries associated with each customer are limited to three loading bays, located opposite the storage and preparation module dedicated to that customer.

“We now achieve 60% direct flow per customer module, with no crossover with other modules,” confirms Eric, “and we haven't had a single lost-time accident on the loading bays since 2023.”

The change that was introduced is proving to be even more fruitful than it originally seemed. The ratio of parcels per pallet is increasing since the area is working with a pallet dedicated to one customer, rather than partial pallets to be dispatched to several customers. Truck filling is improving.

Collaboration between employees is now possible. “We want to take advantage of the specialization by customer module to strengthen the team spirit on the docks. Today, there are truck loaders, forklift operators preparing pallets for loading, palletisers... we now want versatile teams dedicated to a single customer,” Eric explains. His challenge? To build teams that know each other, working with a stable customer, capable of finding solutions on the ground, instead of crossing paths anonymously (and dangerously) on the quays.

DESIGNING THE JUST-IN-TIME PROCESS FROM THE OUTSET

It is complicated to implement Just-in-Time on a flow and equipment that were never designed for it. Walking along the modules up to the dock receiving production, we see abnormal pallet storage between the dock and the customer module racks.

The forklift operators who deposited the pallets there are in fact twice as fast as the large AGVs (Automated Guided Vehicles) that manage high-bay storage. This shows how difficult it is to reverse initial mass-production choices (high racks instead of flat storage, sophisticated AGVs, flows systematically directed to buffer stock, conveyor configuration blocked for the day, etc.). This is the key lesson of TPS: design for Just-in-Time from the outset.

This is what was done for the latest plastics processing unit, where Sodebo manufactures its own plastic containers—Pasta Box pots, meal salad trays, sauce and dressing tubes, etc. The plant was designed with TPS in mind: production is levelled out over a takt, on a just-in-time basis, and stops if the downstream process that consumes the containers is no longer picking them up. Quality is on everyone’s mind: a visual and shared defect library helps prevent defects from spreading.

Whether they assemble salads, bake pizzas, or prepare sandwiches, all Sodebo plants are located on the same site at Montaigu, in the Vendée region. Séverine and I leave Eric to go to So Fresh, which manufactures meal salads.

FROM VOLUME OBSESSION TO CONSUMER-FOCUSED COLLABORATION

In 2018, Sodebo's plants were obsessed with keeping up with their production lines. The only visible indicator was the volume produced, and there was no way of seeing who was working on what.

The Obeya in the plant we are visiting today did not exist back then. Every Friday, the Quality, Safety, Maintenance, Scheduling and Lean managers meet there. “Consumer complaints are the first topic we discuss,” explains Freddy. The team is now fully confident about the importance of identifying and fixing problems and freely discusses the week’s failures.

The indicators on the wall also facilitate discussions on safety and demand vs capacity, which are fundamental issues for stabilizing operations and building confidence at the front line, health and safety.

“There’s always a machine problem, a material problem, a new scenario on a line,” explains Freddy. “I've worked hard to improve the stability of our teams. You can’t train or learn if the operators on a line are constantly changing.” He has established a permanent core team for each line and each shift, with a team leader capable of maintaining a steady pace and quality, and to whom seasonal or backup operators, who are themselves better trained, are assigned when the pace needs to be increased.

This new approach has enabled So Fresh to improve its productivity (Parts per Person per Hour or PPH) by 5.6% compared to last year.

Freddy and his team also analyze the changes underway, which always carry risks. They are also indicative of what the team has in mind: are they on the right track? Are they focusing on the right problems? The three executives (Patricia, Marie Laurence and Bénédicte), who visit the Obeya once a month, never fail to discuss this with him.

JUST-IN-TIME FOR FRESH PRODUCE – NOT A SIMPLE EQUATION

We are standing by one of the lines, where Just-in-Time has been the subject of much thought. Sodebo plants manufacture in continuous flow on huge single- or multi-product lines. Batch size and flexibility of production resources are, therefore, key to delivering the right product when it is requested.

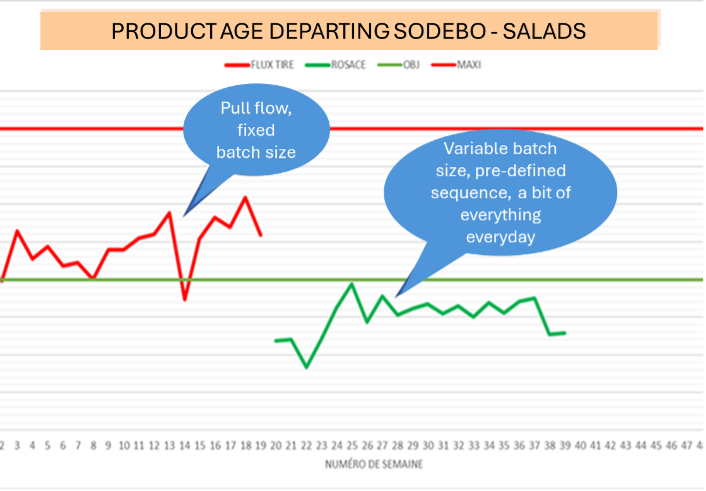

Séverine explains: “We don't sell screws and bolts. If our Sales & Operations Plan (S&OP) tells us to make 25,000 salads per day and the firm order for the day is only 20,000, we have to store 5,000 fresh salads: for us, that’s one day lost on freshness. And we are obsessed with freshness.”

An experiment with a levelled and firm S&OP was attempted in 2019. The approach was typical: the daily load was not affected by the customer’s firm order, production was stabilized on a takt time, and the effort was levelled. Operators on the lines were no longer subject to customer variability. However, the approach generated too many discarded products, as they were too close to their use-by date to be sold.

Sodebo has worked and is still working on an alternative approach. To minimize the change-over time between two products, a sequenced approach used in chemistry has been introduced to optimize the cleaning time between products. Product C is easily launched after B, but takes more cleaning time after A, hence an ABC sequence. This has made it possible to produce smaller, variable-size batches and to introduce an EVERYTHING - EVERYDAY approach, which Freddy is closely monitoring.

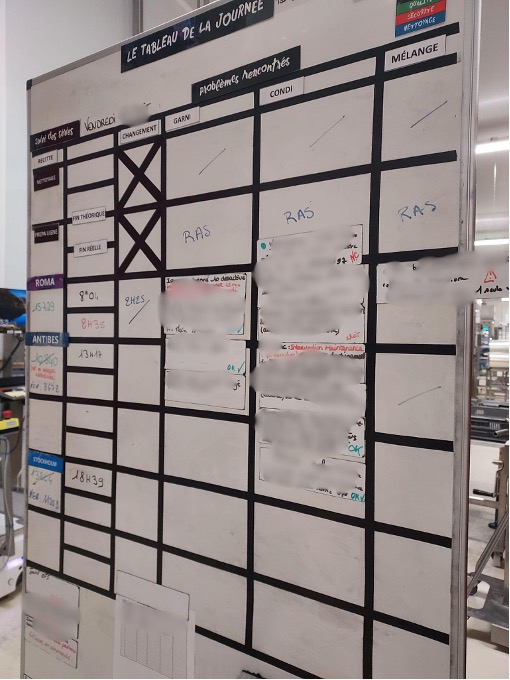

He shows me the line’s Daily Board, a concept that was completely unknown back in 2018. It is where a true, visual, and shared analysis of the day’s production takes place, and where problems are presented, discussed, and worked on.

“Occasionally, we still discover problems three weeks later, but it’s becoming increasingly rare,” smiles Freddy. “I find the exercise very useful and I attend two or three daily board analysis sessions every week.”

Problem-solving rooms are also available near the lines. Marianne, Sector Manager, is working on a quality issue: the absence of ham in some salads. “The possible causes are discussed with the line operators,” she says, “which allows them to think about the problem. For example, as a result, an operator will find a new, more efficient setting for the line.”

Not all manufacturing problems are related to lacking workmanship, poor material quality, or cutting issues. They also stem from product design, and here too, collaboration between the R&D and plant departments has evolved considerably.

IMPROVING EXISTING PRODUCTS, AND INNOVATING

We are now with Claire, Chief Engineer at Goodwich (sandwiches). Back in 2018, R&D focused solely on innovation, drawing on the research and expertise coming from the Marketing Department.

The introduction of a Chief Engineer—a concept borrowed from Toyota—changed the game. With Sodebo facing challenges even in its dominant positions, the Chief Engineers, each working on their own product range, are working on product architecture, today’s value points, tomorrow’s trends, and on conducting in-depth teardowns of competing products (materials, dosage, cooking, appearance, taste), both to improve existing products and to prepare for innovation.

I am impressed by the visualization that covers the walls of the R&D space, whether it is used for defining the concept of a new product or for closely monitoring the launch of another. Everything is done to see, understand, and act together. This allows the Chief Engineer to clarify what he or she has in mind, share and exchange ideas, and be challenged on them.

“Customer complaints are reviewed in detail every week in the Market Development department and at the plant. A recurrence of problems with what we believe to be a strong consumer expectation triggers the opening of an A3,” Séverine tells me.

This groundwork allows the team to question some of their assumptions: “Sodebo's 3,200 employees are regularly invited to take part in blind tests comparing one of our products with a competitor’s product: we face reality, we learn, and we challenge ourselves all the time.” The underlying obsession, as can be seen on the teams’ display boards, is to better understand consumer preferences.

The Chief Engineers also seek to capture or anticipate changes in consumer expectations. “Anticipating underlying trends is of fundamental importance,” confirms Bénédicte Mercier, one of Sodebo's three executives, who has just joined us. “It is crucial for new products, of course, but also essential to know where to invest in terms of production capacity.”

THE HELICOPTER VIEW

This kind of challenge is the focus of many conversations between the executives and their Executive Committee, of course, but also with their Lean Officer, Séverine.

Daily discussions with managers on major issues, weekly meetings of the Executive Committee's Obeya, and field visits with managers enable Séverine to facilitate what Freddy Ballé, who co-authored The Gold Mine in January 2010, used to call the management helicopter, between the company’s challenges (broad vision) and the reality on the ground (micro details).

One example? The integration of seasonal workers during peak times, or more generally of new operators, has always been a major challenge for the company. The labor pool is limited in Montaigu, and recruitment is difficult. This makes it essential not to lose new recruits at the end of the week due to a lack of proper integration. This recurring global challenge has been addressed by Séverine. Using the TPS, she partnered with executives and managers to create efficient onboarding programs that taught new hires technical skills and standards, including dojos and integration workshops.

Seven years after committing to a lean approach, Bénédicte confirms how much Just-in-Time, Obeyas and gemba have truly transformed the company. “One thing is clear,” she says with smile. “TPS has significantly improved our ability to identify and address the problems that need solving.”

Rediscovering the joy of a job well done, discussing and learning from mistakes, designing new production lines using just-in-time from the outset, analyzing the competition in detail (even if it hurts), stabilizing teams to increase collaboration... The Toyota (Thinking) Production System is everywhere at Sodebo, with a shared credo: developing human capital leads to better products.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

CASE STUDY – An elementary school in Budapest is trying to bring innovation to the education by harnessing the power of lean thinking combined with a solid digital strategy.

INTERVIEW – At the recent European Lean Summit, we sat down with a senior executive from Fiat Chrysler Automobiles to learn more about the company’s World Class Manufacturing approach.

FEATURE - Whether an organization pursues a lean transformation often depends on the early financial results - the low hanging fruit - it's able to achieve. This article offers a model to meet business needs while ensuring a transformation lasts.

FEATURE – The author shares a story from a training session at the gemba, which contains a couple of important lessons on the Training Within Industry method.

Read more

NOTES FROM THE VIRTUAL GEMBA – Despite a 40% drop in sales and the looming prospect of having to furlough part of its staff, this French company is finding in lean manufacturing an ally to fight the current crisis.

NOTES FROM THE (VIRTUAL) GEMBA – This small manufacturer is relying on Lean Thinking to keep the business running during the Covid-19 crisis, overcome the disruption in its supply chain, and even innovate.

INTERVIEW — Ahead of next week’s Lean Global Connection, one of our speakers talks about how the comprehensive lean transformation of Indonesian food company Garudafood.

CASE STUDY – This hotel in Spain has been able to leverage Lean Thinking in its restaurant to successfully adapt to the new Covid-19 regulations enforced in the country, becoming more efficient along the way.