A blueprint for lean programs

FEATURE - Projects or programs? The authors discuss why Lean Thinking should go beyond piecemeal operational improvements, as a transformative strategy that balances today’s demands with future adaptiveness.

Words: Michael Ballé and Julie Chevalier

Where should we search for results in lean? Looking back, it’s easy to say it enabled us to achieve this or that – stories are told after the fact. Companies that we know firsthand have doubled or tripled their turnover in the last 15 years whilst maintaining profitability and navigating endless crisis from COVID-19 to IPOs. Their CEOs will say that lean is a big part of their success story, but they will also express frustration at getting their own managers to see it as a priority as events unfold. That lean is a fantastic support to a company’s ambitions is obvious in hindsight, not so much when you’re in the thick of it, as the pressure to just get the job done, deliver short-term results and hope for the best is relentless.

Imagine you’re a middle manager in a service company. A large customer is regularly complaining about your lead-time and price. As you consider each unhappy e-mail, you find nothing extraordinary – there is always a valid contextual reason for what happened and you’re clearly not worse than your competitors. So, should you:

- Apologize, explain and promise you’ll do better next time… and then move on to running the day’s business with its usual lot of burning fires? (Path 1)

- Or apologize, explain and promise that you’ll do better next time by investing in a program of gemba walks and kaizen events to figure out what is really ailing this customer and how to improve both the deal and the relationship? (Path 2)

Of course, there is also a third path of hunkering down, ignoring it all and expecting the problem to go away as long as people show up in the morning and do their job (which is really what happens in most places). Your CEO tells you to follow Path 2 but:

- You haven’t got time or resources right now.

- You’re unsure how to do it.

- You don’t see how this would solve your long list of immediate problems.

And these are absolutely valid points. As a sensei once told one of us, “you need to balance today and tomorrow. If you only take care of today, you won’t have a tomorrow but if you only look at tomorrow without taking care of today, you won’t have a tomorrow either.”

The question is how? Here’s what we know so far:

- Traditional management lets you ride market conditions. You grow and make money when times are good, you stall and lose money when times are hard, and eventually some unforeseen crisis will kill you. Until that happens, the stock market is oversensitive to positive projections in the short term and merciless in the middle term.

- Point optimization with savings-type projects is common because you can easily project return on investment: here are the points we need to improve, here are the consulting resources we can invest in, and this is the payback we expect (and many consultants are eager to sell it to you). We also know that these programs always fail within two-to-three years (the savings don’t appear in the accounts and what has changed under duress with the consultant’s pressure goes back to normal) and probably worsen the situation overall by making the business more fragile rather than more robust.

- Lean transformation programs deliver on their promise to CEOs who are fully committed to understanding, practicing and teaching lean, but these are few and far between. Such results are difficult to quantify because they are impossible to disentangle from market conditions, unless you are clear-eyed enough to make projections “with lean / without lean.”

What then do lean CEOs seek from lean? Where do they look for it? How do they try to find it?

CEOs know that if their business is viable, its basic value proposition is okay – with different levels of market margin (some markets are profitable for all competitors, like tech until very recently, while others are very low margin, like anything that has to do with automotive). They also know that their performance will be impacted by how well the business runs day to day and how well it responds to market shocks. They also know that, to ensure further business, they need to renew their value proposition with innovation, which means making gutsy and tricky choices.

In this sense, building on Jim Morgan’s formula for a successful management system, I would argue that, from the top, performance breaks down into three key components:

- The business’ positioning in its market.

- The organization’s culture.

- The firm’s operating systems.

This, in turn is supported by actionable levers:

- Smart choices to get a better market positioning.

- Leadership behavior to sustain a positive can-do culture.

- Improvement activities to support the operating system.

To lean CEOs, lean offers a framework to handle these very complex dimensions of running their business:

- A lean strategy of quality and wide line-up to satisfy every customer segment and flexible operations to respond better to variety.

- The Toyota Way as a canvas for leadership behaviors.

- The Toyota Production System as a system of improvement activities to keep the operating system moving forward.

To sum up, what CEOs seek in lean is not just daily operating performance, but also the adaptiveness to respond to the inevitable crises that will happen in their markets in a VUCA world and the strategic capability to open options in the future for innovation and pivot. To look for these, they strive to clarify strategic challenges (which challenges do we take up, which do we ignore, what are our options, how do we go about it?) and develop internal leaders who will themselves support a lean culture. They realize that piling one lean project on top of the other won’t do the trick and that they need a more robust transformational program of lean activities to accompany their operating system.

What would such a program look like? Thirty years of studying how Toyota went about it and of conducting lean experiments gives us a pretty good idea of how to do it. Of course, it starts with going to the gemba and visualizing processes to solve daily problems:

The next step is to organize and support kaizen activities for all people every day, such as kaizen workshops, quality circles, suggestions follow-up and so on.

The third step is to teach front-line managers to distinguish “good” kaizen, which delivers value to customers or makes life easier for the teams, from “bad” kaizen that reinforces the bureaucracy – this is an essential step to start building the right kind of culture by developing the leadership muscle of orienting towards customer satisfaction and employee engagement rather than working around problems and reinforcing bureaucratic controls.

This leads to look at executive changes. Department leaders and heads of functions make process changes all the time to optimize how their function works, but in most cases someone’s solution is also someone else’s problem (visualize what happens when HR changes a policy). Functional changes create cross-functional problems that can cripple the company, but that can also be avoided through honest communication and be tempered by kaizen opportunities. This makes our fourth step of the program: share executive changes across functions and solve the resulting problems for the teams.

The fifth and final step is a common recognition of the structural wastes of the business. We’re not talking about the waste of the time spent looking for your favorite pen, but an understanding that whatever operating system is in place to deliver value, it will carry with it unavoidable waste that most companies consider a “normal cost of doing business”. A car dealership will need to hold inventory, a B2C business will lose some unhappy customers, large industrial installations will have unutilized capacity, and so on. As the program allows us to discuss kaizen opportunities through visualizing the TPS, these structural wastes will progressively be recognized and understood by the leadership team, which can then orient kaizen efforts towards eliminating them. That is the transformative part of the program.

From this perspective, one can see how lean projects that are not part of the more comprehensive vision of a lean transformation (concentrating instead on optimizing this or that process) can make the company less adaptive, not more. In such a scenario, a company may recognize the structural wastes in its operating methods, but will see them reappear regularly with each new external change (they are inextricably bound with how the company does business). Adaptiveness is, therefore, the result of constantly fighting these wastes in changing circumstances.

The same sensei who taught one of us the importance of always seeking to balance the needs of today and the needs of tomorrow would also have us always go back to look at the steps of an operator in a workstation: “one meter, one step, one cent.” And he was right, of course. The slightest change on the line will affect how operators need to move around value-adding work. But it took me decades to realize this only applied in a high takt-time production line condition. Operators who, for example, build one complex machine a day won’t be bothered as much by steps as they will be by missing parts or engineering mistakes. Waste types, such as Ohno’s famous seven wastes, are tied to a specific operational set up. They’re a good starting point, but what about the waste of talking to customers in the wrong tone for any B2C company, or choosing the wrong sales channels (as Nike has recently done by focusing away from stores and trying to do all its business online, badly damaging its brand presence in the process)?

To reap the promised benefits of lean, we must look up from the toolbox (without ignoring it) and ask ourselves fundamental questions: what do we seek from lean? Where will we look for it? What do we expect to find? Daily process performance through greater process control is not transformative – too often it only leads to more bureaucratic pressure. Performance and adaptiveness through embracing a lean strategy, lean leadership behaviors, as well as a lean operating system are. Getting there, however, requires a full rethink of how we “do” lean in practice and drawing the lessons from our many experiments and long experience with lean initiatives. True Lean Thinking is the path to greater performance, greater engagement and ultimately a more sustainable society. We must look towards the horizon and seek that path in order to one day find it.

Learn more about the lean path to adaptiveness at the upcoming Lean Global Connection. Register here for free.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

RESEARCH - Offering us a glimpse into how the human mind works and into Toyota's approach to people engagement, this article tells us how to create a better working environment for our employees.

FEATURE — Lean Thinking is redefining agriculture by turning farms into systems of continuous learning, boosting productivity, reducing waste, and empowering people through daily problem solving.

CASE STUDY – This Turkish producer of sanitaryware has boosted its quality so dramatically it’s now a player in the German market. It did so by bringing drastic change to its production system.

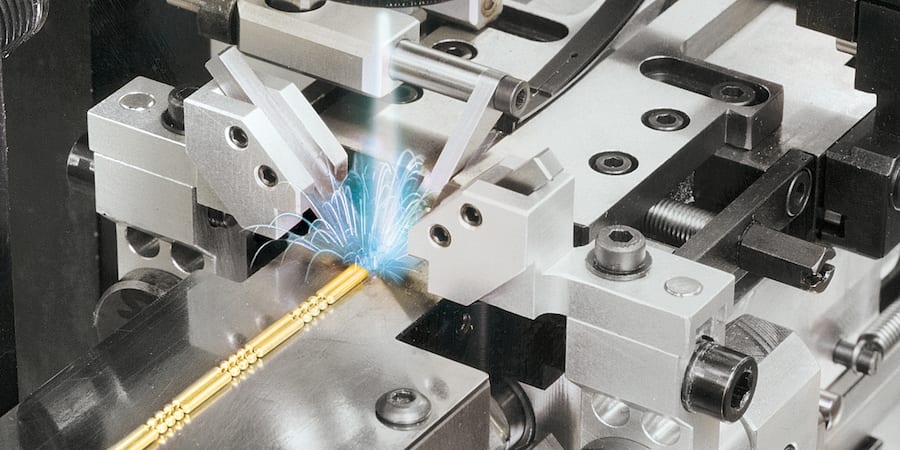

INTERVIEW – Italy-based precision machinery manufacturer Sisma has changed skin many times over the years. We sat down with its general manager to learn how the firm has been able to continuously innovate over the years.