Production as a mirror to the organization

FEATURE – The gemba tells us more than we think. The authors discuss what we need to look at during our walks to understand the impact of non-manufacturing functions on the overall process.

Words: Eivind Reke and Gert Frick

Back in 2019, we were together on the gemba at Volvo Torslanda for a day. We were laying the groundwork for an article on Volvo Cars’ leadership training program, which had been developed by Gert. During the visit, Gert said something that has puzzled and fascinated me ever since (for dramatic effect, we recommend you read it with a Scandinavian accent, like the Swedish chef from The Muppet Show): “You know, Eivind, if you study an operation long enough, you can really see the whole organization.” This sentence contains an entirely new perspective of understanding and learning from the gemba.

Gert first heard about this concept during a visit to NUMMI back in the early 1990s, while working at Saab. Toyota Sensei and managers seemed to look at the gemba as a mirror to the rest of the organization. As we have learned from studying the work of the sensei, the gemba is a place to learn where our thinking is working and where it is flawed with regards to manufacturing, product development or logistics. In truth, however, it is also a reflection of the practices in place in R&D, HR, marketing, or procurement. The devil is in the detail and learning to see that detail is an important skill.

BUSINESS RESULTS DON’T COME RANDOMLY

As Deming taught us, we get what we deserve. Even though we often are more lucky than we are good, the results of a business are never random. The better prepared we are, the more predictable our results will be. Value (and muda) in a production chain always materializes itself in manufacturing. It’s also where it's easiest to see it. That’s why we go to gemba and practice genchi genbutsu: if all departments and functions in a company understand the nuances, struggles and requirements of the manufacturing process, a business stands a much better chance of being prepared and understanding its performance. Support departments like HR, procurement and planning influence the conditions unfolding in manufacturing, and it’s vital that they become more aware of that.

THE PULSE OF THE VALUE CHAIN

If we look at the manufacturing process as a continuous flow of value-added activities moving at the speed set by customer needs (takt-time), we can easily visualize how we go from raw material to finished product and challenge ourselves to study the consequences of a new product, new people, new machines, new materials or new suppliers being introduced. Ideally, we would want to produce value without causing any delay or disruptions in the flow: the customer sets the takt time of demand and, through its smooth operations, manufacturing becomes the pacemaker of the company. But, alas, reality is never ideal. Which is why we need to look for what is normal (the smooth flow of value) and what is abnormal (interruptions in the flow of value) and identify the underlying reasons for the abnormality.

So, let’s see how three non-manufacturing functions – product development, HR and logistics – can influence, support or hinder the flow, and how we can visualize this.

- Product Development

In the lean world, we are used to bringing back every example of waste we see to Taiichi Ohno’s original “7 wastes” categorization, often forgetting about another huge source of waste: misconceptions in Product Development. By nature, product development is full of risk and uncertainty that we try to mitigate through things like market research (what does the customer truly value?) or prototyping (will this new feature work?). In fact, many of the LPPD tools available to engineering departments can be viewed as countermeasures to this risk.

Despite our best efforts, however, all products have design issues that are not discovered until the product reaches the production stage – when the tool touches the product and value creation begins.

So, when we are on the gemba studying an operation, what should we look out for in terms of design issues, miscommunications, or misconceptions?

If we observe an operation or service delivery long enough, we will start to see components the operators are struggling to assemble, instances in which they might have to use excessive force or attempt to make the piece fit several times. In service delivery, we might observe awkward steps for the user or the service provider, or steps where the process stops or lags. In all we do, we are guided by the lean idea of creating the smoothest possible flow with the least amount of effort, to achieve what the work cycle sets out to achieve. Ill-fitting parts or awkward moments in the service are signs of possible problems, warning us that perhaps the engineer or service designer had not thought through how to assemble a particular piece or how to deliver a certain part of a service. They might also be a symptom of parts with tolerances that are too tight, combining to create problems for the worker that ultimately could lead to quality issues for the end user. These types of problems typically present themselves as subtle issues on the production or service delivery gemba or in customer complaints but are always worth investigating from a design and engineering perspective. The answer is never clear cut, but at least we get a window of discovery.

- HR

“It's all about the people.” “We make people before we make products.” “Good thinking, good products.” The passion for making things that characterizes a good lean company is only possible if coupled with a passion for developing people. For Toyota, this makes perfect sense, but our Western obsession with separating functions has unwittingly removed HR from the process of “making people”. Bringing HR to the gemba to study the effect of their work can be either fun or painful (quite often it’s the latter, unfortunately), but it is critical either way. But what are the signs that our HR policies may be flawed?

If HR’s task is to find and develop people who will excel at the job they are hired to do, it’s clear that they first need to be able to understand the preconditions of the job: what is required of it and what are the skills and traits we need to ensure it’s done in an optimal way? If someone is being hired to work in car assembly, where the takt time is in minutes or even seconds, the prospective worker must have the right skills and mindset and be able to perform a task within 60 seconds, 60 times an hour. HR must understand what zero defects in combination with respect for people means and how to find the right people for such a demanding job. At the same time, they need to keep in mind that ideally some of those team members will one day have the will and capabilities to turn into leaders.

When you look at your gemba, how is HR supporting the value creators – whether line operators or service providers? Are they absent or are they present? Do they thoroughly understand the demands of the job?

- Logistics

Generally, the first thing managers look for at the gemba is waste. But what about understanding where the waste originates from, such as the muri and mura coming from logistics and marketing?

One of us recently visited a company that had gotten its internal flow in order but was still ordering from its suppliers in batches. This created a mess of broken, late, wrong and only occasionally right parts. Again, in lean, we are studying the details of operations and thinking upside down: where are we not supplying our value-adding workers with the right tools, the right parts, the right skills, muri-free? To reach our ideal scenario here we need to understand how logistics serves the smooth flow of value from raw materials to finished goods.

THE HELICOPTER VIEW

When one Toyota veteran worked with Scania in the early 2000s, he would spend a few days on the gemba, observing. When Gert asked him why, he told him: “Because now I know how Mr Østlyng (CEO of Scania at the time) runs his company.”

This could be easily dismissed as an anecdote. However, the paradox we face is that the humdrums of the gemba, the details of operations, service delivery or customer usage, provide us with a great helicopter view of an organization. The details act as a mirror to the whole. It takes practice, and answers might not be easy to find, but if you are wondering how your HR, logistics, marketing, or product development functions are impacting your company overall, the gemba is always the place to start. So, show respect, observe intently and closely, and ask why. You might be surprised at what you find!

To paraphrase Dave Meier’s sensei Mr. Honda, “Stand here, look. What do you see? Good, look more.” (From Steven R Leuschel’s Sensei Secrets: Mentoring at Toyota Georgetown.)

THE AUTHOR

Gert Frick has been working in the automotive industry since the late '70s and was first introduced to TPS in the early 80s. Now retired, he has been part of transformations at Saab/GM, Scania and Volvocars. During his career he also worked with companies such as IKEA and ABB as advisor and Vice President of JMAC Scandinavia (Japanese Management Association Consulting).

Read more

FEATURE – SMEs represent the backbone of many economies, but few of them contemplate embarking on a lean transformation. The author discusses why and offers some tips to help them embrace lean.

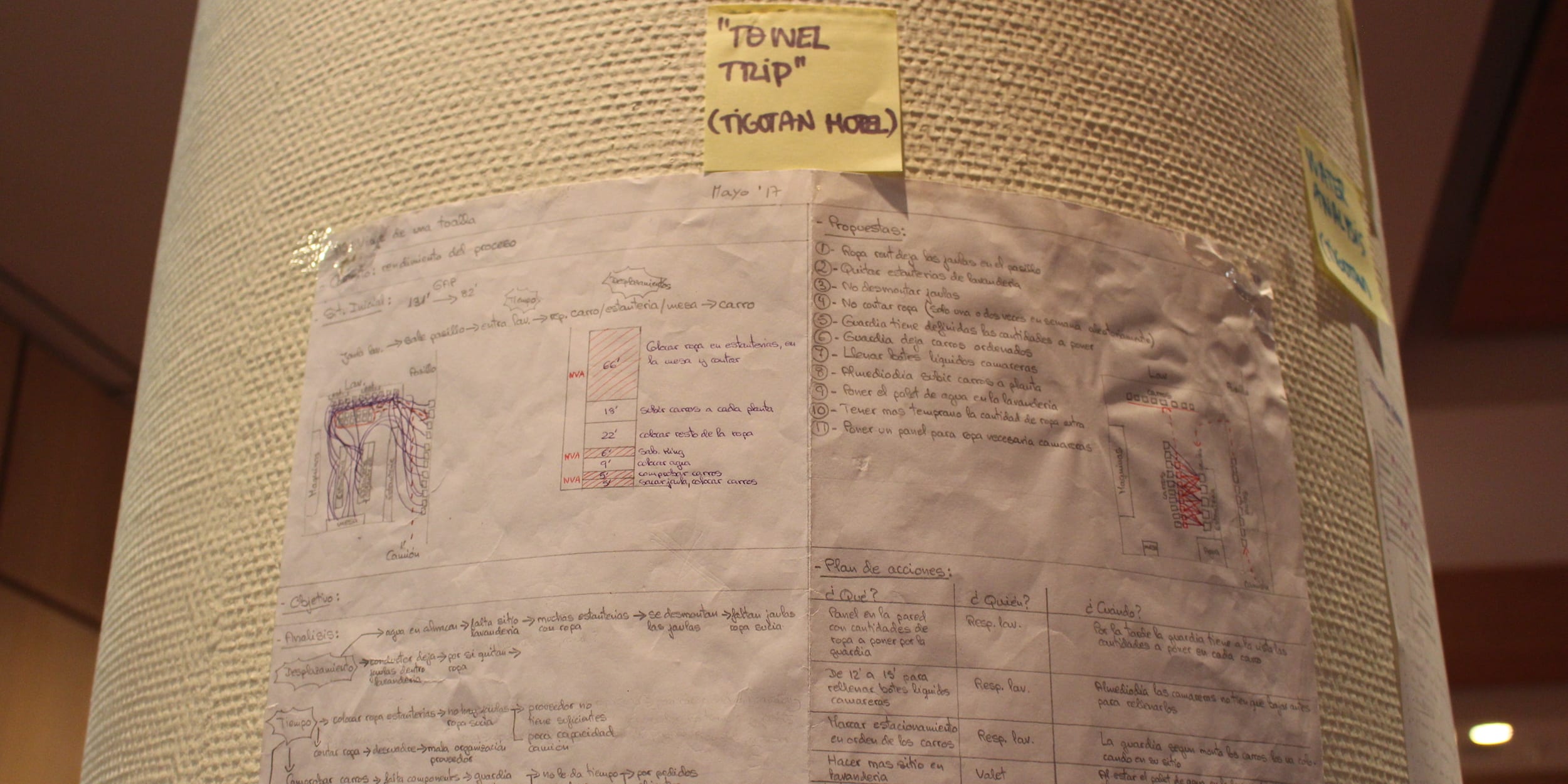

VIDEO – The director of a hotel in Tenerife explains the first steps the team is taking to develop a lean daily management system, and how this connects to the organization's hoshin.

CASE STUDY — Simon, a Spanish leader in electrical mechanisms, went from growth-fueled fragmentation and operational complexity to a coherent, people-centric lean system spanning factories and offices worldwide.

FEATURE – Attracting, developing and retaining talent has become a pressing issue in the corporate world, as new generations show skepticism towards traditional management. Lean is the answer, say the authors.